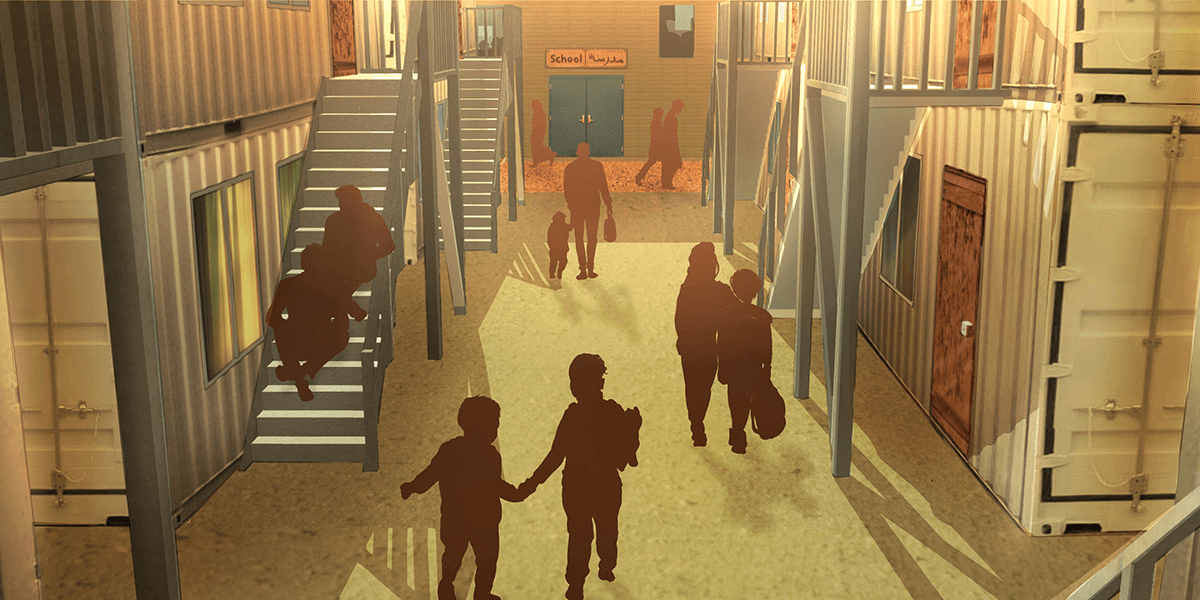

A refugee camp as re-imagined by USC Viterbi undergrad students Stefani Mikov and Emir Ucer. Illustration/Alya Rehman

USC Viterbi undergraduates Stefani Mikov and Emir Ucer want to fundamentally transform the structure of and improve conditions in Syrian refugee camps in their home country of Turkey.

“Refugee camps should typically house 20,000,” said Mikov, a senior double majoring in industrial and systems engineering as well as piano in the USC Thornton School of Music. “Right now, camps in Turkey are holding about 6,000 more than that. Without proper sanitation, plumbing and medical resources, that means that diseases spread rapidly.”

With nearly three million Syrian refugees in Turkey and little sign of the conflict dying down, the international community has been unable to coordinate thus far to set standards and plans for refugees to survive, let alone thrive. However, Mikov and Ucer’s plan may rectify that.

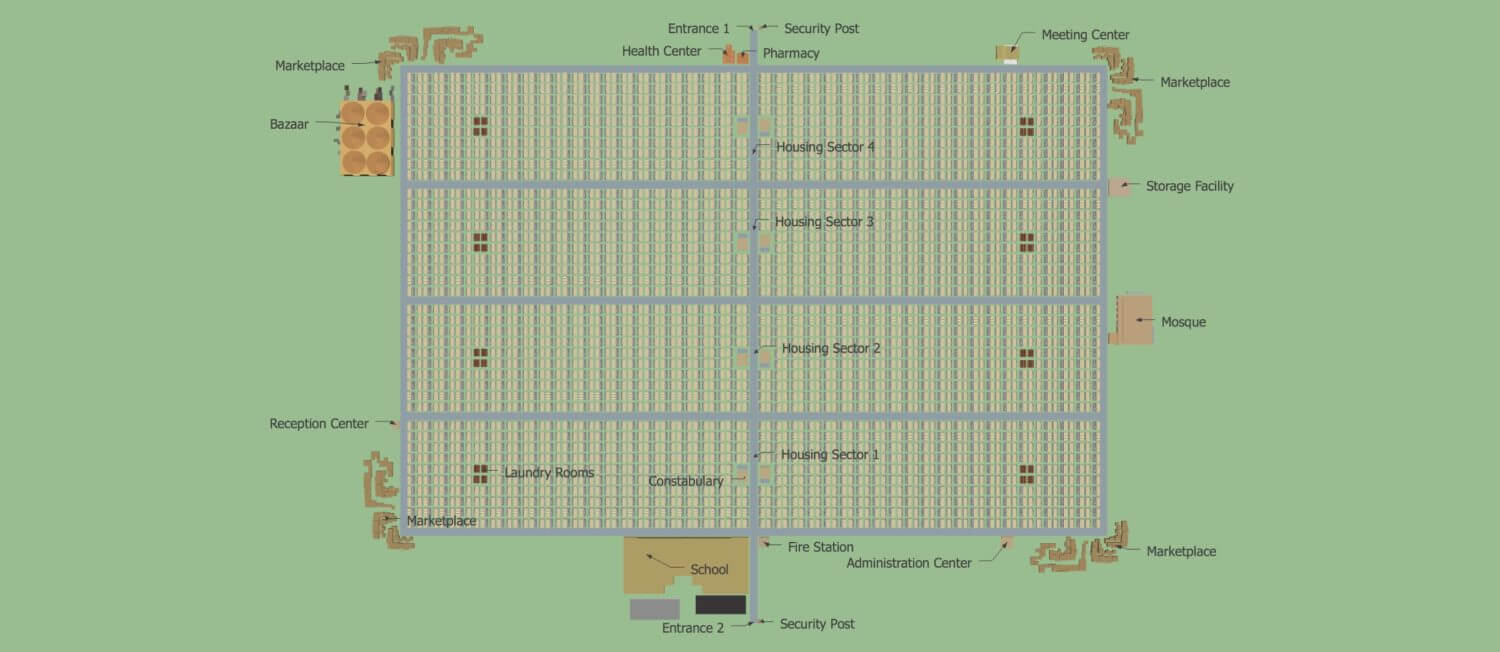

Complete with a fire station, a pharmacy, a clinic, a religious center, internal security, and even a school to teach academics and Turkish to Arabic-speaking Syrians, Mikov and Ucer’s meticulously sized redesign is built around the idea of a refugee camps as a transition place.

“Their fresh, outside-the-box perspective is not always readily available to those in power charged with managing the refugee crisis”

Najmedin Meshkati

“Many of the refugees suffer from trauma once they make it to safety,” said Ucer, who found with Mikov in their research that over half of refugees suffer from PTSD and up to nearly one-third suffer from depression. “Although our plan includes therapists in the health center, some men won’t seek psychological health for cultural and religious reasons. That’s why we also included a mosque, so the refugee community can heal in preparation to reintegrate.”

The pair’s redesign also maintains internal regulation, with security stationed in each of the four, 5,000-person housing sectors requiring fingerprinting. In addition, Ucer and Mikov explicitly designed multiple markets throughout the camp to keep prices low and supply high through competition, rather than fallaciously impose price controls.

A current refugee camp in Ankara, Turkey Photo/ Wikimedia Commons

“A sustainable plan needs both the engineering, economic and ergonomic understanding of camps, but also a cultural understanding,” Mikov said. “Even though southeastern Turkey, where these camps will probably be stationed, is more conservative than Istanbul, it’s important to take these cultural sensitivities into account.”The number of stratified spaces will allow men and women to co-mingle but also to remain segregated by gender, paving the way for a transition from the far more conservative Syria into the more progressive gender norms of Turkey.

Added Najmedin Meshkati, their professor and former U.S. State Department Jefferson Fellow in the Daniel J. Epstein Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering: “It’s so refreshing to see undergrad students like Stefani and Emir so socially and globally-conscious, willing to apply their education to solving wicked problems that are truly among the world’s grand challenges. Their fresh, outside-the-box perspective is not always readily available to those in power charged with managing the refugee crisis. I really think they’re the embodiment of a badly needed and sought after global engineer.”

Overhead view of Mikov and Ucer’s envisioned refugee camp that includes a marketplace, school, fire station, health center, and mosque. Illustration/Alya Rehman

Scouting for a suitable location remains one of the most complex challenges for the establishment a refugee camp.

“We can’t have a camp too close to a war zone, and absolute safety is very hard to achieve as long as the UN refuses to create no-fly zones that could protect the people,” Ucer said.

Mikov and Ucer are currently trying to get their research published in “Ergonomics in Design,” a peer-reviewed quarterly, with an end goal of having their work featured in a Turkish newspaper.

“Right now we’re focused on exposure in the ergonomic community but also in Turkey,” Mikov said. “This first step, getting the Turkish media on board, is key to having our plan manifest itself into life saving reality.”

While Mikov and Ucer understand that media exposure has its limitations in practical application, they eventually hope that their plan reaches the Turkish ministries, who thus far have been in charge of building refugee camps.

“I’ll call my parents in Istanbul, and I ask them what’s really going on with both the diplomatic and humanitarian crises, and they say that they don’t even know,” said Mikov. “No one knows what’s actually happening, so we’re hoping for the best at this point.”

Their plan began humbly enough, the product of a class project for Human Factors and Design, taught by Meshkati. However, now the pair, both Turkish citizens themselves, has a much greater goal than an ‘A.’

Published on January 12th, 2017

Last updated on March 10th, 2017