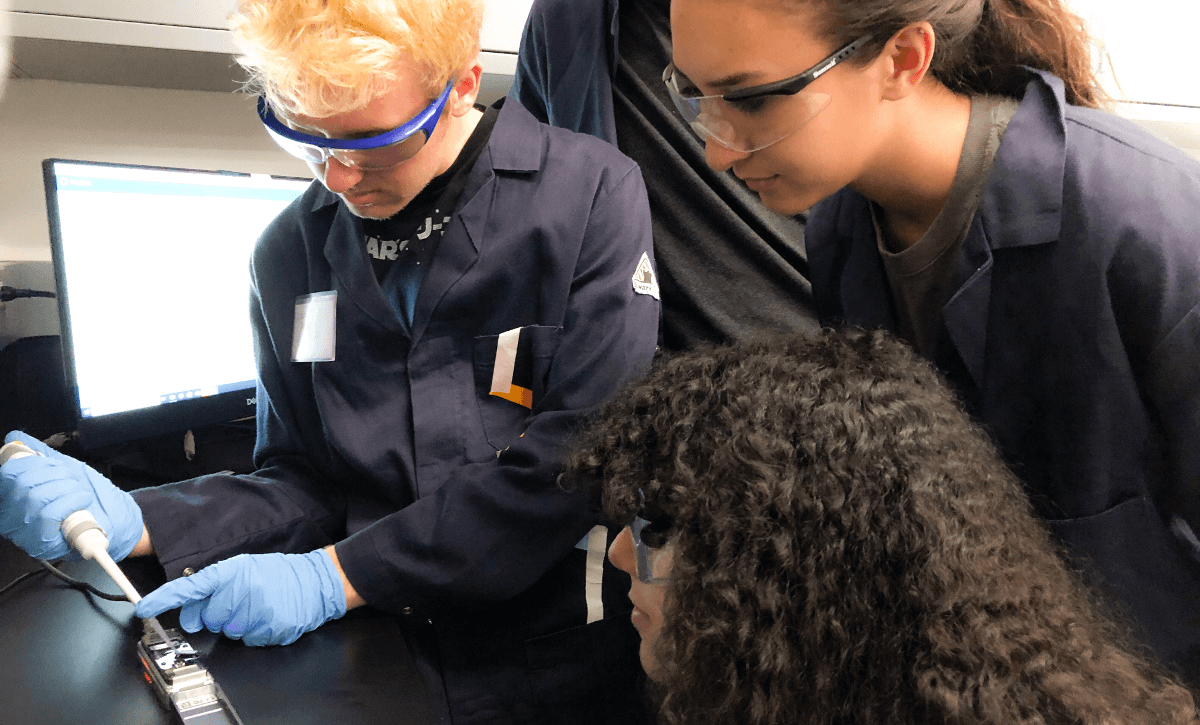

Students Jacob Totaro, Patrick Breslin, Sierra Giles and Carol Navarro loading a sample of DNA onto the nanopore sequencer. Photo/Adam Smith

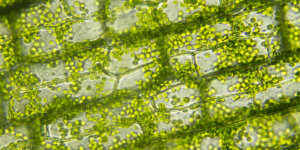

Armed with brand new equipment and lab space, students in the CE 210L “Intro to Environmental Engineering Microbiology” course spent the fall semester investigating a community living right under their noses – their own microbiome. This includes all of the microorganisms, or microbes, living in or on our bodies, including bacteria, archaea and viruses that vary across different body parts and individuals.

One to three percent of the human body mass is made up of microorganisms. Because of their small size, this results in a whole lot of microbes. Bacteria specifically outnumber our own human cells by 10 to 1. And they are not always harmful. Some microbes help our immune system by providing nutrients to cells.

In this lab course, students were tasked with evaluating their skin microbiome. They worked in groups to sample microbes in different locations on their bodies, extract microbial DNA, amplify and sequence biomarkers, and use bioinformatics to compare microbial communities across different sample locations. They were then able to determine what species of microbes were living in what locations and how they compared to other individuals.

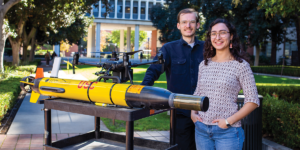

“This is pretty standard work for a research lab like mine, but unique to do it in an instructional lab,” said Adam Smith, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and the class’s instructor. “It’s made for a fun and engaging lab component to my course. I also doubt many, if any, instructional environmental engineering labs are doing DNA sequencing.”

Similar to researchers involved in the NIH’s Human Microbiome Project, students categorized testing locations as oily, dry or moist, depending where on the body the sample was taken. For instance, the forehead was considered oily, while the forearm was dry, and the back of the knee was moist.

Their results confirmed most assumptions: acne causing bacteria was commonly found on the face, while bacteria found in soils was found on the hands. They also discovered that similar communities on different body parts could be explained through their relationships. For example, microbes on the face and forearm may be similar due to a habit of wiping sweat on your arm, while microbes on your arm and feet are mostly different due to limited contact and far proximity.

“DNA sequencing, in of itself, is interesting. Most people don’t get to do that, especially at this level,” said Nicole Arcos, who is majoring in environmental engineering and taking the course. “Professor Smith is really good about teaching not just the principles but the applications as well, which I think is more useful.”

The DNA sequencing process they learned can be applied to the genes of all living things, including humans. But that’s not to say that microbiomes don’t bring a lot to the table on their own. Scientists believe that they can provide further understanding to human health and disease and have been exploring the links between microbiomes and preterm birth, inflammatory bowel disease, and Type 2 diabetes.

Published on December 13th, 2018

Last updated on December 13th, 2018