Essam Heggy uses satellites to study the evolution of water on Earth and across the solar system. (Photo Credit: Essam Heggy)

“In the coming decades, much of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa may have completely depleted their freshwater aquifers – if that happens, all water reserves needed to support life during a drought will be gone,” said Essam Heggy, a research scientist in the Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. I had just walked into his office to discuss his work and this was the first thing out of his mouth. My recorder wasn’t on, my notepad was still in my bag, I wasn’t even sitting down yet! What followed was one of the most impassioned cases for water education that I’ve ever heard. And if you live in Los Angeles, you’ve probably heard a few.

Notice I said water education, not water conservation. Yes, conservation is hugely important. But Heggy is more concerned with making water science an area that inspires research, students, and funding in the same way that something like cancer research does. He understands what he is up against. Most people, in some way, have dealt with cancer on a very personal level. Meanwhile, here in the United States, taking an extra-long shower never killed anyone.

“Water is like a language. You don’t speak it alone, you speak it with others. That’s what looking at other planets and satellites is like: speaking the language of water with our solar system.”

Heggy is part of USC Viterbi’s Arid Climate Water Research Center (AWARE), led by Professor Mahta Moghaddam, the William M. Hogue Professor of Electrical Engineering of the Ming Hsieh Department. This center designs tools to understand and mitigate water scarcity and Heggy has teamed up with JPL and NASA to track water using sophisticated satellite technology. As a planetary scientist, Heggy has been a member of several missions exploring water in the solar system and then re-applying that knowledge right here on Earth.

“Think of Venus as like an early Earth, Mars as a future Earth, or the icy moons of Jupiter like our Ice Age Earth,” said Heggy. Each of these bodies represents a phase in our own planet’s history and by understanding how water evolved on them, we can learn more about its evolution here.

Of course, Heggy puts it more eloquently: “Water is like a language. You don’t speak it alone, you speak it with others. That’s what looking at other planets and satellites is like: speaking the language of water with our solar system.” Only, these days Heggy isn’t so much speaking the language as he is shouting it. And you can’t really blame his sense of urgency. Consider this thought experiment:

“What happens when Egypt, a country of more than 100 million people and a high illiteracy rate runs out of water?” Heggy asks desperately. This is something that could happen soon and the impact on food availability and prices as well as environmental and health conditions would be disastrous. If you think the current refugee crisis – already the largest since World War 2 – has destabilized the world, you haven’t seen anything yet. A disaster like this might call for a stronger word than “destabilized.” When exploitable aquifers disappear, droughts go from crisis to emergency very fast. A two-year drought in a country with no accessible water table means that lives are seriously threatened. According to Heggy, people will migrate…or fight, to survive.

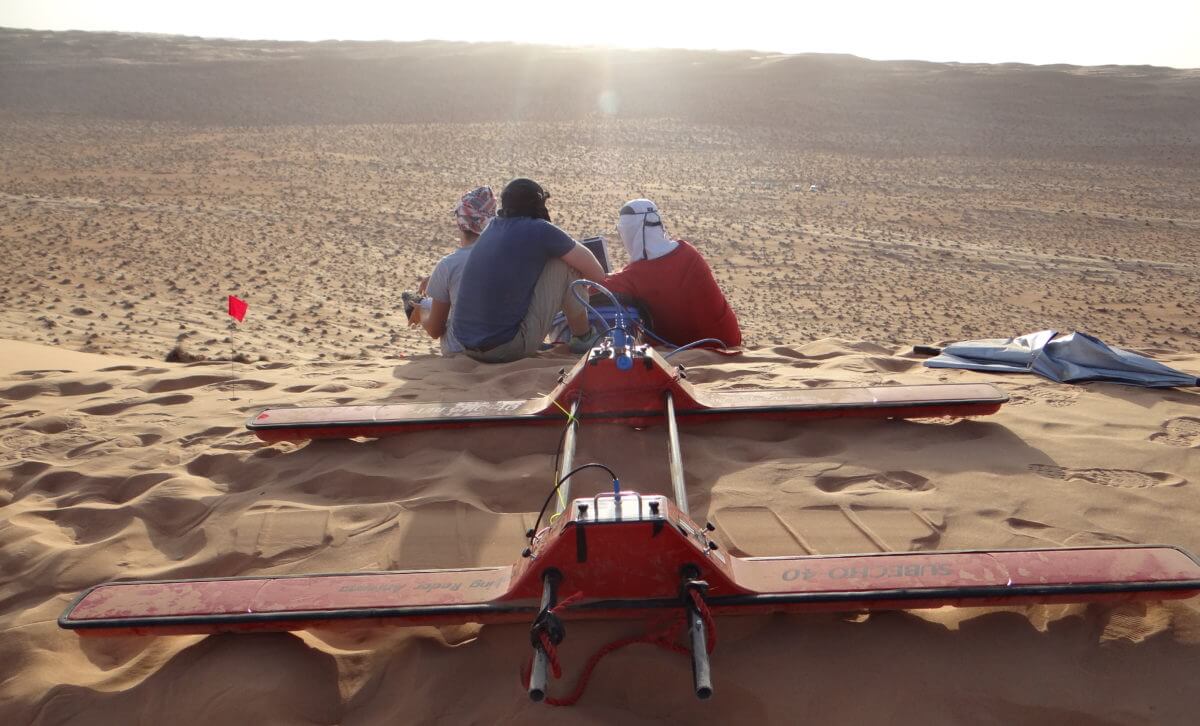

Heggy in the Arabian Peninsula analyzing satellite data on underground water. (Photo Credit: Giovanni Scabbia)

Heggy’s research was recently published in the November 2018, volume of the journal Global Environmental Change. The paper includes an in-depth analysis of the forecasted water budget deficit and groundwater depletion rates for the most arid countries in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula and the socio-economic implications of such water shortage in the upcoming three decades. According to the findings, three countries in the region are most at risk. Egypt, Yemen and Libya all have GDPs that simply cannot handle the economic impact of the inevitable water shortage. For the Arabian Peninsula specifically, Heggy’s work suggests that the majority of exploitable aquifers could be depleted by 2050, with a total and complete depletion of all accessible groundwater in 60 to 90 years.

Not only would these three countries be at risk, but it is unclear how this would impact neighboring countries in an already volatile region, or what the fallout would mean for the global community. Despite these sobering predictions, when it comes to stories about water on Earth’s deserts, people don’t seem to get that excited. Last year astronomers discovered a 12-mile wide lake of liquid underground water on Mars. You may have read about it; it was all over the news. Jupiter’s moon Europa often makes headlines for the vast water ocean believed to exist below its surface. And yet, as of the writing of this article, exactly zero humans live on Mars or Europa. In fact, humans – over seven billion of us – only live on Earth. This disinterest in Earth’s water is the mindset Heggy is trying to change.

Who better to embrace this field than USC Viterbi – a school devoted to teaching students to use engineering to bring about societal change. A school that happens to be one of the largest and well-respected research institutes in a water-stressed environment.

The silver lining is that water stress in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula isn’t always due to climate change. “Many of the problems we see here are the result of human water mismanagement,” says Heggy. “This means that to address it, we have to invest in human elements.” Investing in human elements means more than charity programs and relief efforts. It means working to make water science a field that isn’t only exciting and respected but also better funded.

Heggy believes this change has to begin with the scientific community. And what better institution to embrace this field than USC Viterbi – a school devoted to teaching our students to use engineering to bring about societal change. A school that just so happens to be one of the largest and well-respected research institutes in the world located in a water-stressed environment.

These society-smashing water challenges may one day come to Southern California. Heggy, originally from Egypt himself, knows firsthand what an important role water resources play in the conflicts of his homeland. “If we’re ever going to stop fighting over there and build more peaceful communities, water science must be part of the foundation.”

Heggy, right, with team members and their equipment in the Arabian Peninsula (Photo Credit: Giovanni Scabbia)

Published on January 24th, 2019

Last updated on February 22nd, 2022