Paul Chiou (left) and Ali Alotaibi.

Mobile applications have all but become the saving grace for the mountains of clerical work in our daily lives. We use apps for everything from scheduling doctor’s appointments to filing our taxes, making everyday tasks quicker and easier than ever before. However, while these apps can be considered convenient for some, they certainly aren’t convenient for everyone.

Although a growing number of people are dependent on their mobile devices for everyday obligations, developers seldom seek to make their apps accessible to people with disabilities. Mobile apps don’t often pay heed to accessibility guidelines and this can make it more difficult for people with motor disabilities and older individuals to use the app, or even prevent them from carrying out those everyday obligations.

Enter Ali Alotaibi and Paul Chiou, two Viterbi Ph.D. students who want to make the process of redesigning apps for accessibility convenient, too. They noticed that a large number of apps on the market had a prominent issue: touch-targets—the portion of the screen you use to interact with the app, like buttons or checkboxes— were prohibitively small, and it was potentially difficult for older people or people with disabilities to use them.

A touchy subject

“Despite the increase in the number of people who rely on mobile devices, surveys still show that a lot of mobile apps remain inaccessible to disabled users,” Alotaibi said. “They have to use mobile devices in order to access information and remain connected to the world, and this became even more important during the pandemic.”

“Despite the increase in the number of people who rely on mobile devices, surveys still show that a lot of mobile apps remain inaccessible to disabled users.” Ali Alotaibi.

Although Google developed a set of guidelines for developers to ensure that touch targets are big enough in Android apps, these guidelines are seldom followed, according to the pair.

“It’s a prominent issue, but these developers are just not aware,” Chiou said. “It’s a lack of awareness.”

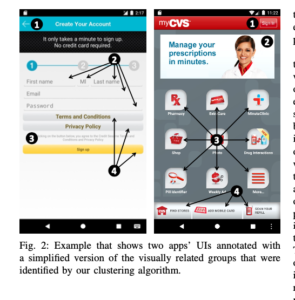

Chiou and Alotaibi saw an opportunity to use their expertise to pursue a long-standing interest in accessibility and developed a program called SALEM—or the Size-based inaccessibility Repair in Mobile Apps— that automatically evaluates the app for size issues and reorganizes the layout with new, larger targets. SALEM uses the Google Accessibility Scanner to identify these targets that are too small, and then generates a host of new alternatives to the app’s current layout.

However, rearranging user interface layouts can be tricky. The way layouts are coded in apps isn’t always intuitive and introducing changes can create a “cascading effect” where other elements overlap or push each other around, resulting in a mess. This is where SALEM’s genetic algorithm comes in. After creating several different alternatives, SALEM assigns each one a fitness score based on how many of these mistakes occur or how distorted the result is. By generating multiple iterations with improved fitness scores, SALEM can “learn” what the best way to fix the problem is.

SALEM uses the Google Accessibility Scanner to identify targets that are too small.

“We designed a fitness function that could basically calculate the quality of each repair that it proposes,” Alotaibi said. “We take all these factors into consideration- the alignment, the positioning, the spacing, size of the element to calculate the quality of the repair.”

After several generations, the champion that earns the highest score is then designated as the replacement for the faulty user interface and ready to be applied.

“It’s really just a way of telling the computer what you want it to do,” Chiou said. “We say, ‘we want you to reorganize these elements and make the touch targets fit the guidelines.’”

Sizable success

After they ran SALEM on 58 different UIs from various real-world apps, the new and improved layouts were presented to people with motor disabilities and older adults, both groups that are disproportionately impacted by size-based issues; Chiou and Alotaibi explained that the goal of this step was to test if the layouts’ fitness scores reflected real-world viability. The results were overwhelmingly positive: SALEM fixed the minuscule touch targets without impacting the interface’s usability.

“What that means is that we were able to fix a problem that does not negatively impact the UI,” Alotaibi said. “We also received some really encouraging feedback from people saying it’s larger, it’s easier to interact with. The study was really overwhelmingly positive in terms of the UI.”

“The research is the first to actually try and fix this problem.” Paul Chiou.

For both Chiou and Alotaibi, accessibility has always been on their minds. Last year, Chiou worked on making web and mobile interfaces more cooperative with Assistive Technologies.

“Accessibility, in general, has been an interest of Ali and mine, and that’s why we chose it,” Chiou said. “For me personally, I have a disability, so it hits closer to home. When I joined the program initially, accessibility technology is what I wanted to do.”

No small feat

The project is the culmination of a fruitful friendship that started when they were in the same Viterbi Computer Science Ph.D. program back in 2018, according to the pair, and SALEM is a passion-fueled product that stemmed from them bouncing ideas off of each other over the years. They also cited the effect that the encouragement and support from their Ph.D. advisor, William G.J. Halfond, had on the project.

“We would not have done this project or any other project without his guidance,” said Alotaibi.

“The research is the first to actually try and fix this problem,” Chiou said. “But there are more and more inaccessibilities that are getting mainstream attention.”

They hope that the tool will act as an easy fix for size-based issues for consumers, as well as help bring accessibility issues to light so that developers might consider implementing more accommodations in the future. The pair has already made some leeway in exposure— they presented their findings at the 36th annual International Conference Automated Software Engineering last November, a privilege reserved for the best in software engineering.

“Our research is super exciting, because we get to apply interesting techniques, in terms of software engineering, and at the same time we get to fix these problems that impact people with disabilities,” Alotaibi said. “Sometimes people don’t appreciate the difficulty some people have with using apps, and developers don’t understand the impact small changes can have.”

Published on May 19th, 2022

Last updated on May 16th, 2024