Dice against blue background. (Photo/Courtesy of Pixabay)

Researchers from the USC Viterbi School of Engineering’s Information Sciences Institute (ISI) have partnered with Purdue University to take part in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)-funded program that seeks to develop the science that will allow AI systems to adapt to novelty, or new conditions that haven’t been seen before.

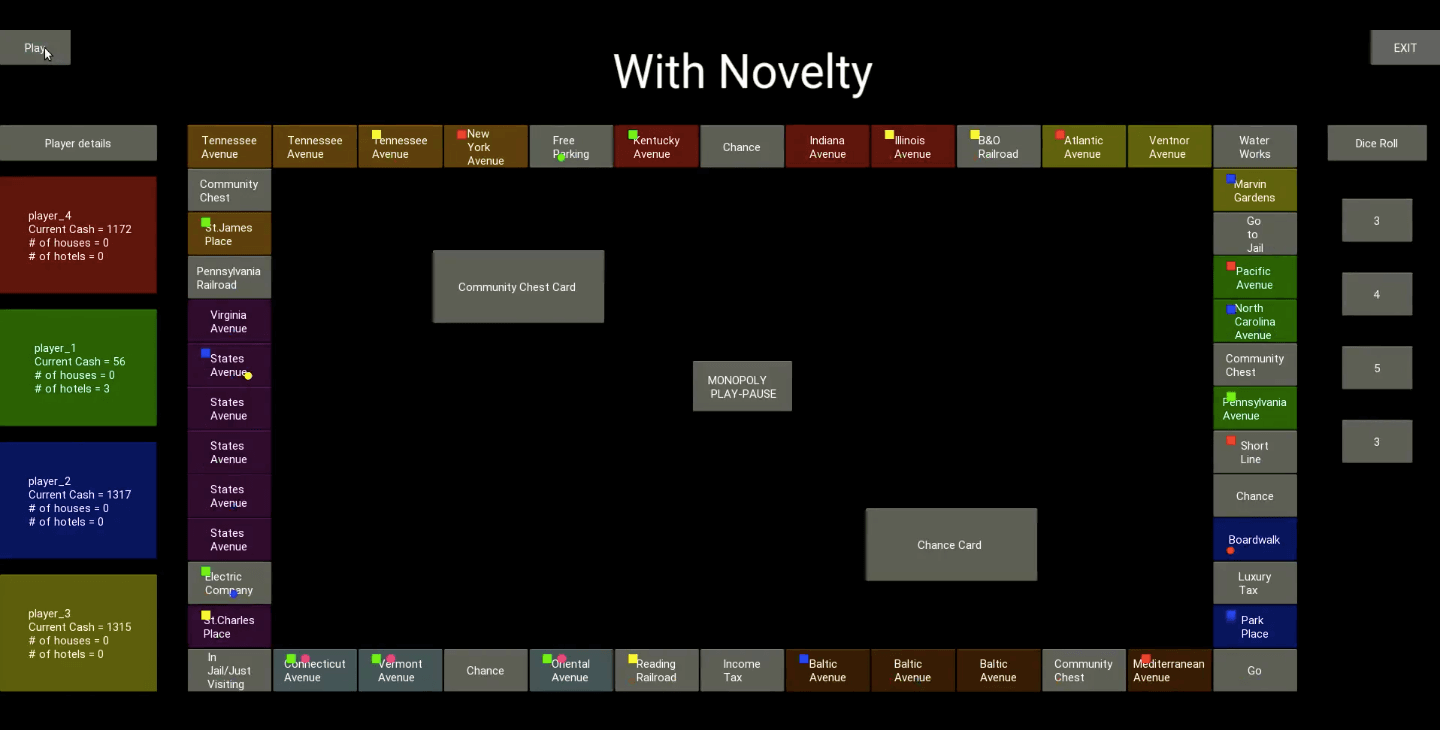

Take an AI that has been trained to play a standard game of Monopoly. What if you change the rules so that you can buy houses and hotels without first getting a monopoly? What if the game is set to end after 100 turns instead of waiting for bankruptcies? These are both novelties which would affect the optimal strategy to win.

And yet, as Mayank Kejriwal, the primary investigator on the project and a USC Viterbi research assistant professor, added, even today the most advanced AIs are ill-equipped to deal with this sort of novelty.

“Even though there have been lots of advancements in AI, they are very task specific,” Kejriwal said. “The moment you introduce changes that the AI is not specifically equipped to handle, you have to go back and retrain the program. There is no general AI, something that can adapt to novel situations. We are really in uncharted waters because there is no science of novelty.”

“That’s the significance of this project,” he added. “It’s not just about improving some specific AI module. By developing a science of novelty, we are laying the foundation for future generations of AI.”

The Science of Artificial Intelligence and Learning for Open-world Novelty (SAIL-ON) program, or SAIL-ON program began in November of 2019 and will continue until 2023. At the program’s end, the Department of Defense hopes to use the research in a range of applications, from autonomous disaster-relief robots to self-driving military vehicles. The USC and Purdue collaborative team has been allocated $1.2 million from DARPA, and will likely receive more as the program goes on.

In some respects, AI has already surpassed human capabilities. Kejriwal cited AlphaZero as an example — a computer program that uses machine learning to play board games such as chess and Go, can now beat even the most advanced human players.

Unfortunately, because of an inability to handle novelty, most successful applications of AI such as AlphaZero are limited to tasks with fixed rules and objectives.

If we want AI systems to operate successfully in real-world environments, we need them to handle things they haven’t seen before, Kejriwal added; the real world is full of new situations.

“COVID-19 is a perfect example of a novelty,” Kejriwal said. “It’s not like we are trained to deal with this, but we figured it out and adapted. An AI would not have known what to do.”

As an example, he spoke about an AI security system whose purpose was to protect an online retailer from different types of cyber-attacks. When the pandemic caused people to panic-buy toilet paper from the retailer, the AI saw more such requests than ever before. Not understanding the influence of the pandemic, the system assumed it was under attack and blocked all of the valid requests. Faced with this novel situation, the AI was unable to adapt.

There are infinitely many possibilities in a real-world environment, Kejriwal said, which means there’s no way an AI can anticipate everything that might happen. “Short of anticipating every single possibility, how do you actually learn to deal with novelty in the same way that a human does?” he asked. “In this project, we want to establish an entire paradigm for doing this, which doesn’t exist currently.”

While the program aims to develop general solutions for handling novelty across many fields, each group chose specific domains for testing. Researchers at ISI are working in the domain of board games, specifically Monopoly, while their counterparts at Purdue focus on ride-sharing.

In the context of Monopoly, like the real world, there are infinitely many ways to introduce novelty.

In addition to the possible rule changes mentioned previously, Kejriwal explained that you could add more dice, have different paths to choose from, alter the objective of the game, or even introduce incentives for teamwork.

“The AI has to adapt to all of this, and it doesn’t know beforehand what types of novelties can happen,” he said.

The digital Monopoly game created by ISI / Screenshot Courtesy of Mayank Kejriwal

Similarly, for an AI system that governs a ride-sharing app, there are so many possible real-time changes that there’s no way to account for them all individually. Vaneet Aggarwal, an associate professor at Purdue and one of the project leaders, talked about the importance of adaptability for AI in this field.

“We want the algorithms to be scalable to different things that happen around us,” he said. “It should adapt to different countries, different cities, different rules, as well as any unexpected events like road blockages.”

Aggarwal added that the underlying science of novelty developed in the project would be useful for far more than just ride-sharing or game-playing. “It would be applicable in any place where decision-making has to happen under uncertain conditions,” he said.

Published on July 31st, 2020

Last updated on May 16th, 2024