Nagarajah received a $25,000 prize to advance the device, which prevents plastic debris from flowing through neighborhood drainage systems and polluting the oceans. Photo/Lauren Silberman.

Walking through the busy streets of his hometown of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thiloshon Nagarajah noticed the plastic waste choking the open drains that run through the city. Like many areas with underdeveloped sewage systems, in Colombo, wastewater, debris and litter—including plastic bottles and bags—flow straight through ditches or channels into the ocean.

Plastic in the oceans is a serious problem, killing more than 100,000 marine animals and 1 million seabirds every year. As an environmentally conscious engineering student, Nagarajah knew he had to do something to help.

Now a master’s student in computer science at USC, Nagarajah has developed a device that stops plastic debris from flowing through neighborhood drainage systems and polluting the oceans. His mantra? When it comes to plastic pollution, prevention is better than cure.

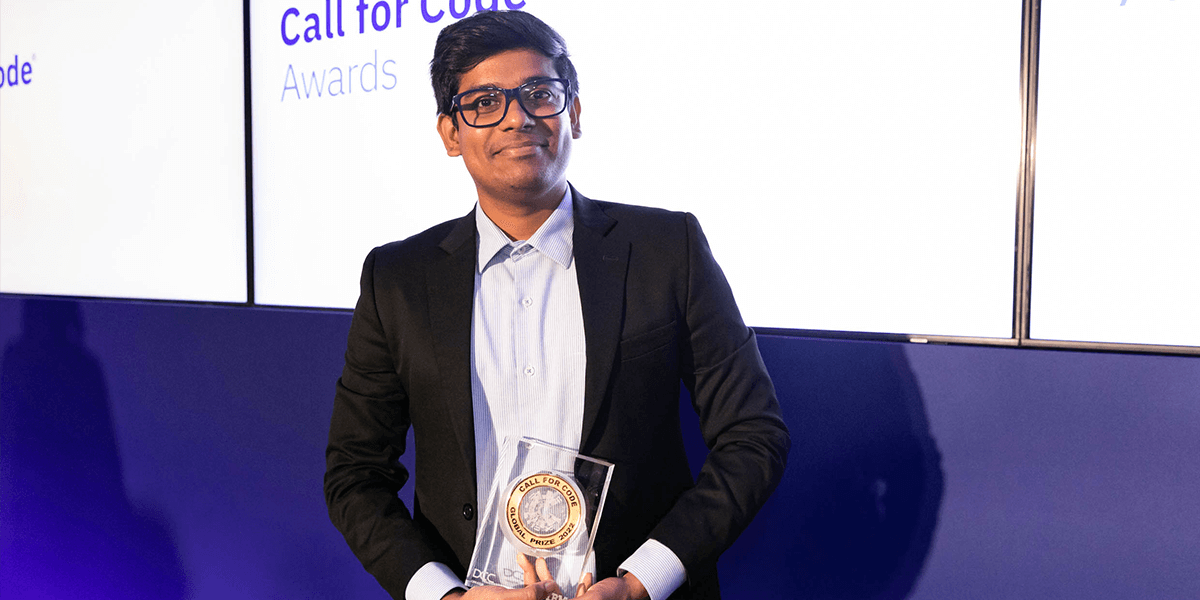

Nagarajah is a master’s student in computer science at USC. Photo/Tamoghna Sarkar.

“There are a lot of large-scale projects that try to capture already existing plastic, which is great,” said Nagarajah. “But the best thing is to stop it where it originates. We have to stop it from ever reaching the ocean in the first place.”

In mid-November 2022, Nagarajah discovered his project was one of the top 5 finalists for the IBM Call for Code Global Challenge among thousands of entries around the world, including professional teams.

At an awards ceremony in New York on December 9, Nagarajah placed first runner-up at the competition, taking home $25,000 to advance the tech, called Pπ, along with implementation support from IBM engineers.

Simple yet effective

It wasn’t Nagarajah’s first brush with success. In December 2021, Nagarajah and his team won first prize in IBM’s Call for Code Education Innovation Case Competition for their e-learning mobile app that allows students around the world to access remote learning without requiring fast or reliable internet.

Last spring, he was taking a course on autonomous cyber-physical systems when the Call for Code competition email landed in his inbox. The timing was perfect. He knew exactly what he wanted to develop: an autonomous device to prevent plastic pollution.

“In under-resourced countries, costly, large-scale clean-up projects are all but a dream,” said Nagarajah. “I knew we needed a simple yet effective plastic clean-up initiative focused on everyday consumers.”

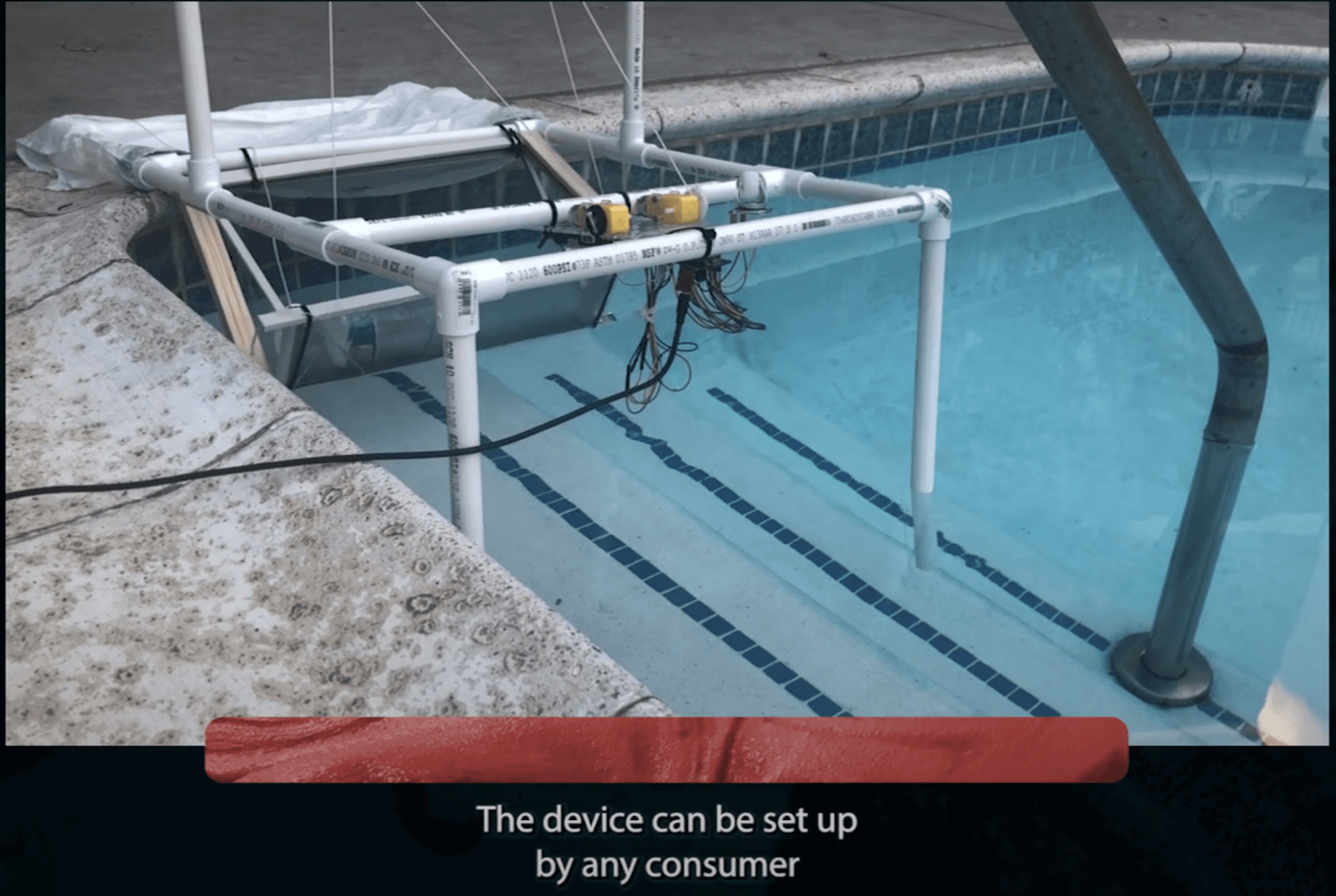

Nagarajah tested the final prototype in the swimming pool of his student housing complex.

Nagarajah developed the tech from scratch over the course of three weeks, testing the final prototype in the swimming pool of his student housing complex. Inexpensive (the prototype cost just $30 to build) and lightweight, it can be set up by anyone who wants to stop plastic debris flowing through their neighborhood drainage systems.

“Each house has its own drainage that connects to all the others,” said Nagarajah. “You can place the device in the drainage managed by your house, so you have control over it.”

Powered by AI, the device’s camera monitors for inbound debris, intercepting harmful products like plastic, polythene and tin. A mechanical arm with a wire mesh is then deployed to catch the incoming debris, which is stored and removed periodically by the user.

Nagarajah built an AI model that uses object recognition to differentiate between organic and plastic waste in the water canal. Once it identifies plastic, the AI sends a message to the motor driver to start rolling an electric motor, which starts spinning the wheels and transfers the plastic to the bin.

The user can monitor the device usage to see the estimated sea life saved by their device on an app. Nagarajah estimates that 400 marine animals and birds could be saved by using just one device for a year.

Making a real change

Nagarajah believes this is the first product of its kind aimed at individual consumers. While wire meshes have been used to catch plastics around the world, the system is usually implemented by authorities or NGOs.

“Anyone can buy this product from the market and keep it next to their house and open drainage system,” said Nagarajah. “This is mainly aimed at good Samaritans who want to make a change.”

In Colombo for instance, Nagarajah estimates that 19 devices placed at each of the city’s drainages could capture plastic pollution of 100,000 consumers—around 2 tons per year. He hopes communities all over Sri Lanka, and beyond, will be interested in using the device to clean up their own waterways. He has already moved on to the next phase of development: making the app self-sufficient.

“Right now, when the IoT device finds the plastic, it stores the information in the device itself,” said Nagarajah.

“When a phone goes near the device, it sends the information to the device and the cloud. The next version will be connected to a nearby wi-fi network to send the information directly.”

This marks the fifth Call for Code Global Challenge, a worldwide, multi-year initiative that inspires developers to solve pressing global challenges with sustainable software solutions. Nagarajah hopes his impact will be felt far beyond the borders of his own country.

“If you’re a vegan, or if you’re an activist, you are an individual working to make a change. If you want to stop plastic pollution, this instrument will help you do that,” said Nagarajah.

“Even a few of these instruments can make a huge change strategically placed in points across the city. I feel like it has the potential to make a real impact and a real change.”

Published on January 18th, 2023

Last updated on May 16th, 2024