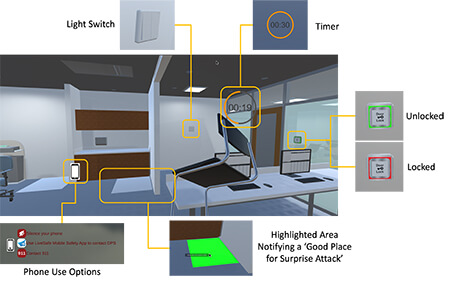

VR rendering of lobby environment at Keck School of Medicine of USC, with timer indicating active shooter threat

During the pandemic, we came to see healthcare workers as frontline workers, risking their lives on the first line of defense. However, the truth is that healthcare workers have always been frontline workers, exposed to danger on a daily basis – whether the so-called “reactive violence” of a patient’s sudden response to a diagnosis, or the targeted violence of a planned attack.

According to a 2022 FBI report, the number of active shooter incidents in the U.S. increased by 96.8% between 2017-2021 and by 52.5% from 2020-2021. Moreover, healthcare has now surpassed law enforcement as one of the most dangerous fields in which to work; healthcare workers are five times more likely to be victims of workplace violence than any other industry.

Kelly Busta, senior threat assessment officer at Keck Medicine of USC, is well aware that effective training for such incidents is crucial for de-escalating a situation and preserving lives. She saw an opportunity to enhance safety at Keck through new and more immersive trainings and received a grant from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for that purpose.

“In the context of a healthcare environment, the prescribed approach of ‘run, hide, fight,’ doesn’t take account of the full complexity of the situation,” Busta explained. “Doctors and nurses have a responsibility to care for their patients, so the way they train has to be more nuanced, helping them to navigate difficult decisions.”

With the guidance of Erroll Southers, associate senior vice president of safety and risk assurance, Busta was introduced to a team including Burçin Becerik-Gerber, chair of the Sonny Astani Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering (CEE), Gale Lucas, research assistant professor at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies, and CEE Ph.D. candidate and programmer Ruying Liu.

The team has previously conducted experiments using Immersive Virtual Environments (IVEs), with the goal of discovering how dynamic factors impact human responses to emergencies. By modeling the built environment and simulating the behavior of both the adversaries and the crowd, researchers are able to measure participants’ responses in realistic ways that are not possible outside the lab.

Becerik-Gerber is an expert in user-centered responsive and adaptive built environments, while Lucas’ training in psychology informs her research into human-computer interaction, affective computing and trust-in-automation. Liu developed the technology for the IVE platform, and she also played an important role in experiment design, data collection and data analysis.

During focus groups with first responders, law enforcement and security experts in the first phase of the project, it became clear that a parallel issue was at stake: the fact that effective training for active shooter incidents is critical for optimizing survival. With this in mind, and with the support of Busta’s initiative to enhance campus security, the team set out to test whether VR active shooter training could help users improve decision-making and maximize survival in critical situations.

Interaction demo for IVE active shooter training

“To achieve high realism, we created a virtual replica of a real hospital building using the Unity engine,” said Liu. “We are now staging control experiments to quantify the extent that IVEs enable a deeper sense of connection with the true stakes of an emergency, in comparison to comparatively passive video and lecture formats. Our studies are showing that greater levels of interaction and immersion significantly helps people to learn experientially, respond with flexibility and ultimately retain knowledge for real-life application.”

For ease of access, the VR training is also accessible via a desktop computer rather than a headset. In addition to certain rote actions – such as silencing a phone, contacting 911, turning off light switches – participants are challenged to make decisions in ambiguous and rapidly changing circumstances. Should a hallway be blocked with furniture, or would that impede others trying to escape? Should a door be opened to an individual calling for help, if accepting would expose multiple patients to danger?

“Traditional training methods often rely on fixed and sequential content that leaves little room for autonomy,” said Becerik-Gerber. “In contrast, our IVE platform employs a behavior-based storyline where trainees are given the freedom to explore different behavior options and uncover new sub-stories. This approach acknowledges the highly dynamic nature of active shooter incidents, where situations can progress quickly, and multiple options may be equally viable.”

An autonomous feedback system provides real-time tracking as participants work against a clock, gaining points and buying time depending on the efficacy of their decisions as they interact with the objects and avatars around them. Rather than simply highlighting errors or providing binary pass/fail metrics, the time-rewarding feature encourages trainees to perform safety actions quickly, prolonging the survival time until law enforcement arrives.

Compassion is also a key consideration. Although a healthcare worker might be compelled to attack a shooter in a real-life situation, the team realized that enacting this virtually could be distressing for those in the caring professions. While realism is paramount, trigger warnings help to manage content exposure.

VR rendering of patient treatment room

“I personally came to the project not just with the hope of working towards safer buildings, but also for the opportunity to understand how VR could be used as a tool to undertake research that would otherwise be costly, complicated and emotionally distressing,” said Lucas. “I think this project is a great case study for how VR can enable us to conduct research in an ethical way that we wouldn’t be able to explore otherwise. “

Not only does the VR training have the potential to be more impactful than non-immersive media, it’s also more cost-effective than traditional immersive training methods; the full-scale on-site re-enactments that are typically only offered to emergency response teams. The accessibility of the platform re-casts all stakeholders – from doctors, to patients, to security staff – as first responders with the shared responsibility of personal and collective survival.

Furthermore, the project exemplifies the way that research can have an immediate practical impact – trialed first on the USC campus, then adapted and scaled for wider application. “Threat management on campus is complex, and a lot of effort goes toward educating community members,” said Busta. “We’re thinking in different ways and producing novel types of training that are improving our preparedness. With our VR project, we’re entering an innovative space.”

Published on September 11th, 2023

Last updated on August 28th, 2024