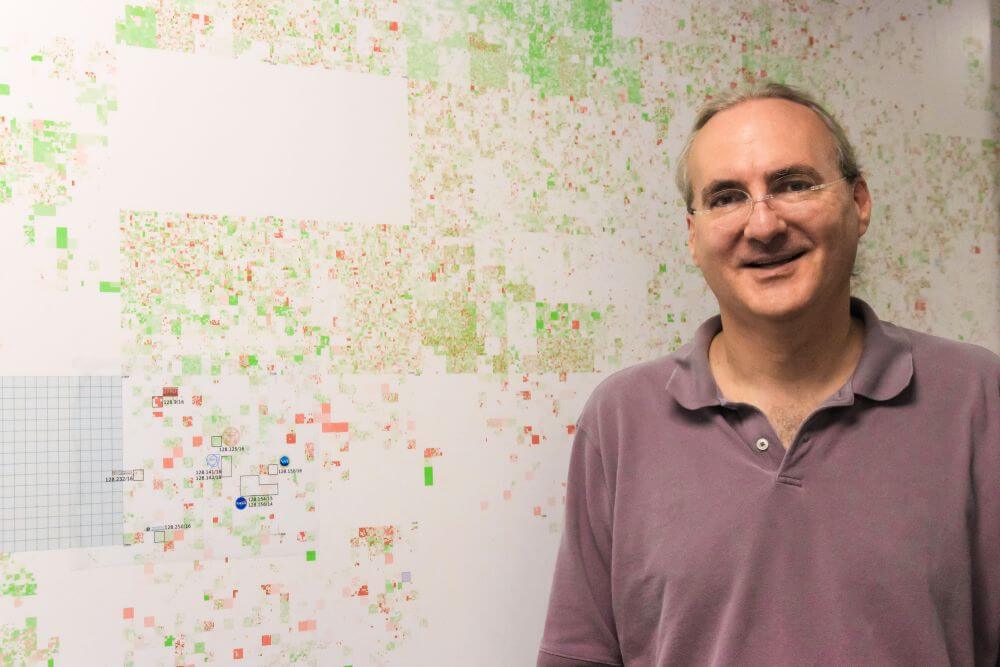

John Heidemann stands in front of a map depicting the whole internet address space, comprising 4.3 billion internet addresses, which was mapped by Heidemann and his team in 2011.

On October 29, 1969, the internet was born. Forty-eight years later, its influence on the world is ubiquitous. In 2017, the number of internet users around the world has surpassed three billion, connecting 50 percent of the world’s population.

ISI has had a unique vantage point from which to view the meteoric rise of the internet. As a creator of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network ARPANET, the network that would later become the internet, ISI invented the Domain Name System (DNS), developed core internet standards, and managed DNS functionality for decades.

But what forces are shaping the internet today, could it ever be shut down, and how secure is it really? In honor of International Internet Day, we sat down with ISI research lead John Heidemann, who has spent more than 20 years studying the internet, to find out more about this revolutionary invention.

1. Who controls the Internet?

The answer is no one and everyone. By definition, the internet is an interconnection of independent networks. But there are some central things that keep it cohesive, such as standards about how information is exchanged. One example is the Domain Name System (DNS), a directory of domain names that can be thought of as the internet’s equivalent of a phone book.

So, who controls the DNS? That’s something the world has wrestled with a lot since the founding of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), an entity that spun out of ISI, under the auspices of the U.S. government’s Department of Commerce. In the last two years, the Department of Commerce decided to terminate oversight of ICANN. Currently, ICANN is an independent organization, which responds to international stakeholders, like internet service providers (ISPs), internet users and the government.

So, you could say ICANN controls one key aspect of the internet— but it does so collaboratively. Like a lot of things, ICANN and the internet only work because everyone agrees to make it work.

2. Could we shut the net down?

I would say technically, yes, parts of the internet could be shut down. But it’s highly unlikely in the U.S. I think the general consensus is that in the U.S., where we have freedom of speech, the internet is weaved into the fabric of everyday life and any positive consequence of turning off the internet would be overwhelmed by the large negative consequences and disruption it would bring.

On the other hand, you can look at other countries where the government has indeed shut the net down. Back in 2011, after weeks of protests the Egyptian government cut off nearly all access to the network. Last year in Iraq, the government shut the internet down for a day to prevent cheating during exams. So, a nation state with central control of its ISPs could technically shut down the net. But in the U.S., our telecommunications industry is large and fairly dispersed, so it would be difficult to imagine that happening here.

Another question is whether an individual could shut the internet down against your will. There have been other events, like a large denial of service attack on Estonia in 2007, which had a major effect on the internet of that country. Could hackers shut the internet down in the U.S.? Again, it’s pretty large and diverse and decentralized, so it would be challenge. But there have been threats in the past— I think most people would be skeptical, but disruptions can happen.

3. Is the internet getting more or less secure over time?

There is both good and bad news about internet security. Personal computers are generally getting more secure thanks to automatic updates, but embedded computers and the “Internet of Things” could pose a major security threat. There are millions of devices like home routers, web cameras, baby monitors or smart thermostats that have no built-in updates, which leaves them vulnerable to attack.

For instance, the recent Dyn cyberattack was launched by someone who hacked into embedded devices. But the really scary thing is not the millions of devices that exist today, it’s the millions of devices that will be purchased in the next year. Let’s hope those devices are better able to take care of updates. I do think embedded devices vendors are learning the same lessons as we did with operating systems in the 90s, but they have some distance to go to catch up to personal computers in terms of security.

4. How big is the net?

This has been the subject of my research for more than decade, and it’s a surprisingly subtle question, since the internet means a lot of different things. Should we count your home internet connection, and all the devices in your home, including your current cellphone and the three old cellphones sitting in shoe box? My group has looked at measuring the public-facing net, gathering data for more than 10 years.

We’ve tried to develop estimates of how many devices are actually connected to the internet at any given time. Our current best estimate is around 800 million, increasing from 400 million when we started this analysis 10 years ago. That number is the devices connected to the internet right now, but there are probably easily 10 times more devices than that, so this is a conservative estimate.

Just like we work hard to get good demographics from the U.S. census every 10 years, I think we need to do the same thing with the internet. You need to understand the economics, security threats, opportunities, and progress made in order to make the internet safer and more reliable in the years to come.

5. Internet speeds get faster every year. Is there a point at which it will plateau?

I would cautiously say yes, it will plateau; I think people are satiated. But I say this cautiously because people are also very clever about using bandwidth in different ways. Like the misquote of Bill Gates that “nobody will ever need more than 640K of memory.” Well, as it turns out, people figured out how to do quite a bit with more memory. Will people figure out how to do more with more internet speed? If our goal is to consume media content, which is the largest bandwidth consumer, we’re doing quite well, as seen by the rise of streaming. But I would be intrigued to see where it could go from here.

6. Could we run out of bandwidth?

Unlike wires into my house, cellphones are limited by physics— there is a limited amount of wireless spectrum in world. Each country regulates wireless spectrum— the U.S. had billion dollar auctions to cellphone companies a few years ago. But fundamentally, there is a limit to how many bits you can send through the air, because we all share that one spectrum. We’ve become good at getting most out of wireless spectrum that we have today, but that capacity will always be more expensive than wired because it’s fundamentally limited.

Some people are worried about a “capacity crunch” as more data is sent over more wireless devices. What seems likely to happen is that people will start to change how they use their devices, holding off watching that high-definition video until they’re on wi-fi. And of course, we will work to make more efficient use of bandwidth have with new protocols and engineering.

7. What would happen without DNS servers?

DNS servers resolve names like “google.com” into IP addresses used to communicate with, for example, Google servers. They’re very important, because nobody remembers those IP addresses, which are just a stream of numbers, but everyone remembers names like “google.com” or “facebook.com.”

As a thought experiment, if you took DNS away, the internet simply wouldn’t work. Before the DNS existed, there was a big list of all the numbers and all the names, which they would hand around once a day. That worked when there were 500 computers on the internet, but I would wager that it wouldn’t work so well today.

As told to Caitlin Dawson.