Remedy Team Members (from left to right): Rohan Jeni Varghese, Hannah Lee, Isha Sanghvi, Vivianna Camarillo, Jake Futterman, Ashwan Kadam. (NOTE: Team members not in this photo are Nicole Tamarov (USC), William King (Duke), Yuanyang Lu (UCSD)). PHOTO/HANNAH LEE.

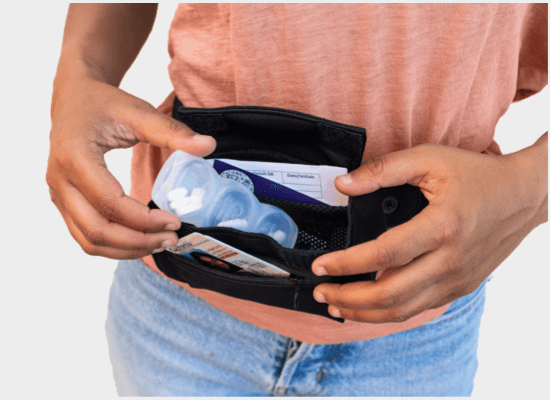

In USC Viterbi School of Engineering course CEE 486, students, who have been tasked with creating engineering solutions to community problems, are repeatedly told, “live a day in the life of the user you’re developing a product for.” For Hannah Lee and her collaborators, that meant hours of extensive research interviewing healthcare providers, physicians, and end-users for their envisioned innovation: portable prescription medicine storage for the unhoused via a soft, flexible pouch that can be worn comfortably on your person.

Interviews and surveys with medical professionals, including with Keck School of Medicine of USC Director of Street Medicine Brett Feldman, pointed repeatedly to a lack of consistency in the healthcare of individuals living transiently.

Said Lee, a human biology major at USC, “When we spoke to Dr. Feldman, he shared that first of all, he can’t find the patients sometimes, but at the same time, they aren’t getting regular treatment because their medication is often stolen.”

Other physicians shared that prescribing certain medications, like insulin, isn’t safe, because of the lack of temperature-controlled storage on the streets.

A member of Los Angeles Community Impact (LACI), USC’s first student-run consulting organization to focus on non-profits and socially-minded organizations, Lee along with neuroscience major Isha Sanghvi enrolled in CEE 486 after other LACI members shared their experiences with it. They began with a team of six, but three members moved on, leaving Lee, Sanghvi, and recent alumna Vivianna Camarillo.

“The class felt like a great way both to tackle big picture issues while also being user-first,” Sanghvi said.

While the first iteration of the class took students to a refugee camp in Greece, COVID-19 restrictions limited the scope of the 2020 – 2021 academic year for students across the world. Instead of traveling to identify spaces in which the students could have an impact, they looked closer to home.

Said Sanghvi: “The pandemic really highlighted the structural health inequities that existed in healthcare. I felt really helpless for the first half of the pandemic, and I wanted to find a way to sustainably address some of the problems that arose, because I was young, healthy, and in a pretty privileged position to give back.”

With a firm commitment to working in the healthcare space, the team moved forward with interviews to learn more about the difficulties medical professionals faced seeing patients, effectively treating them, and committing them to consistent treatment plans.

“When we spoke to Professor Feldman, he described challenges that we never really heard of – despite being attuned to homelessness in Los Angeles. The specific problems he was describing were so new and we were very much like, ‘how do you even go about solving this challenge when you can’t even find the patients?’” Sanghvi said.

The more the team investigated, the more the issue of medication being stolen out of unhoused peoples’ backpacks or tents showed urgency as a first step in helping unhoused individuals achieve better healthcare.

No More Orange Bottles

The Remedy team prioritized user needs and input to better understand product viability. From pilot programs to focus groups, the team has tested several prototypes and identified further issues that need to be addressed for this solution to truly be accessible to all.

“At first we didn’t think about things like accessibility,” Lee said. “But a lot of unhoused patients have difficulty with fine motor skills so even opening the orange pill bottle is really hard because it requires two completely able hands.”

A prototype of Remedy’s soft pouch for pill storage. PHOTO/HANNAH LEE.

Taking the product from concept to manufacturing has required shifts in design. But a major roadblock in scaling up operations is the availability of funds.

“We need money for pretty much every process, like prototyping, 3D printing, large scale manufacturing – so that became the biggest limiting factor. Currently, we have a 500-order backlog that we haven’t been able to fulfill,” Lee said.

Now with awards from the Strauss Foundation, Athena Challenge and Min Family Challenge, Lee said they hope to develop two teams: one focused on the pill container and one focused on insulin and temperature-controlled storage.

At the same time, the Remedy team has three ongoing pilot programs; they will test prototypes in Madison, Wisconsin, New York City and in Los Angeles, where they will shadow providers weekly and help collect data.

“I hope we can encourage more genuine innovation that puts unhoused patients first,” Sanghvi said. “Our best ideas and features for the product came directly from conversations with unhoused patients about their lived experiences. My work with Remedy has helped me better see a space in which social entrepreneurship can improve unhoused patients’ health outcomes.”

Published on August 3rd, 2022

Last updated on August 11th, 2022