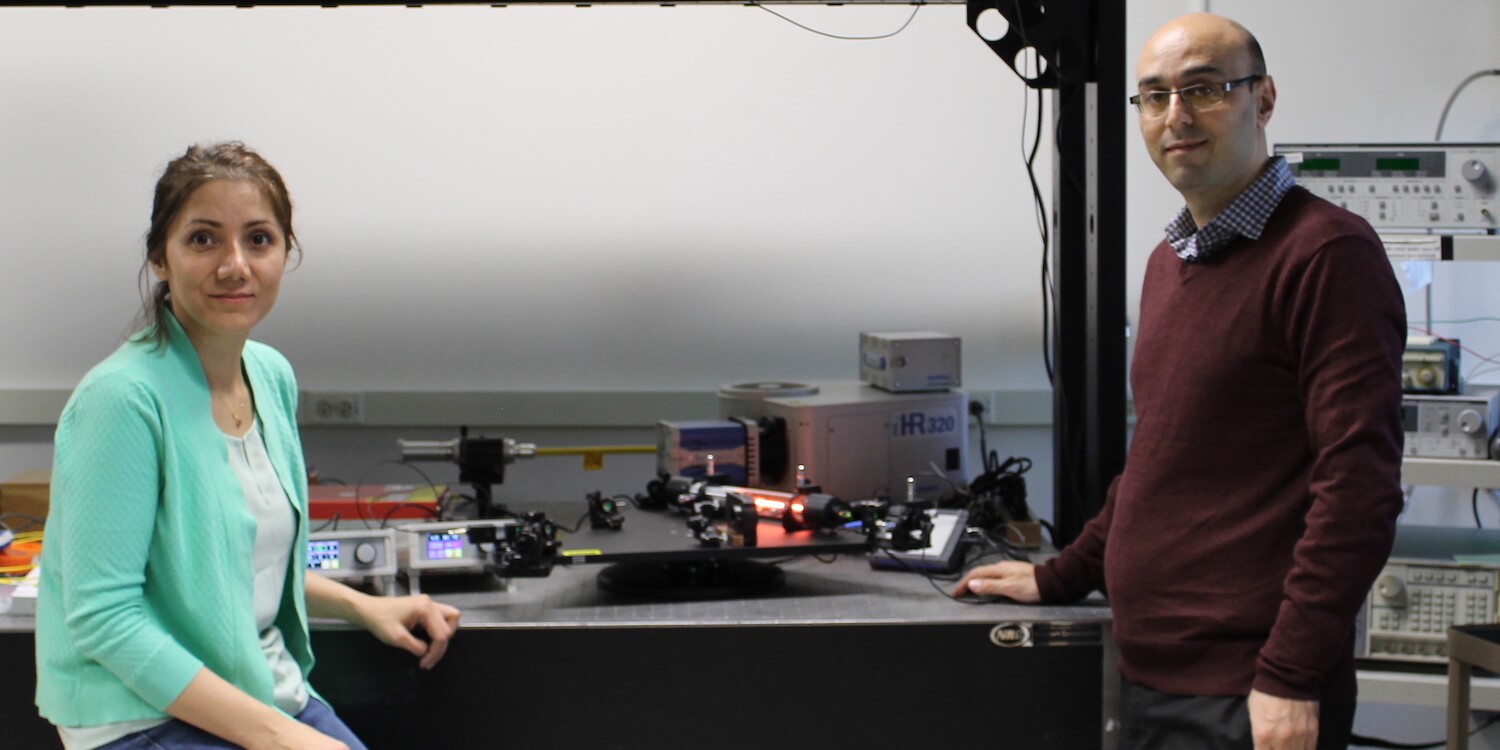

Professor Mercedeh Khajavikhan (left) and post-doctoral scholar Mohammad Hokmabadi with the new optical gyroscope developed in their lab (PHOTO CREDIT: USC Viterbi)

In a recent article published in Nature, Mercedeh Khajavikhan, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and the IBM Early Career Chair, and her group, in collaboration with a team from the University of Central Florida, have shown how to design a new generation of more sensitive optical gyroscopes. Gyroscopes are rotation sensors that are used in a variety of applications involving positioning and navigation. They are part of our smartphones and are extensively used in robotics, medical imaging, virtual reality, computer games, autonomous vehicles, and drones.

Navigation and automation have become an indispensable part of technology today. Take a self-driving car, for example. Much of what allows the vehicle to navigate safely and efficiently is the ability of the onboard technology to understand where the vehicle is and where it is going in relation to the world around it. In other words, its frame of reference. However, in many cases, the frame of reference in question is rotating along with the vehicle. The earth itself is a great example of a rotating frame of reference. A gyroscope measures the rate at which a frame of reference is rotating, thereby giving the car a better understanding of where it is in relation to the world around it.

“We hope that our work will be used towards the demonstration of a new generation of small foot-print and batch fabricable on-chip ring laser gyroscopes that could be potentially used in a host of consumer, industrial, and tactical applications.” – Professor Mercedeh Khajavikhan.

Sagnac effect is the physical principle behind the operation of optical gyroscopes. In a rotating frame of reference, two light beams traveling in opposite directions in a ring-type path acquire a relative phase shift that is known as “Sagnac Phase.” Measuring this phase allows one to determine the rotation speed of the frame of reference.

In general, optical gyroscopes are more sensitive than micro electro mechanical system (MEMS) gyroscopes and are naturally resilient to shocks and mechanical movements. These features make them very attractive for a variety of applications. However, it has been difficult to make integrated optical gyroscopes that are small enough to be used practically in new technology while also maintaining high sensitivity. “In order to measure very small rotation rates, an optical gyroscope must be relatively large in size. This has been the main drawback towards miniaturizing optical gyroscopes” Khajavikhan said.

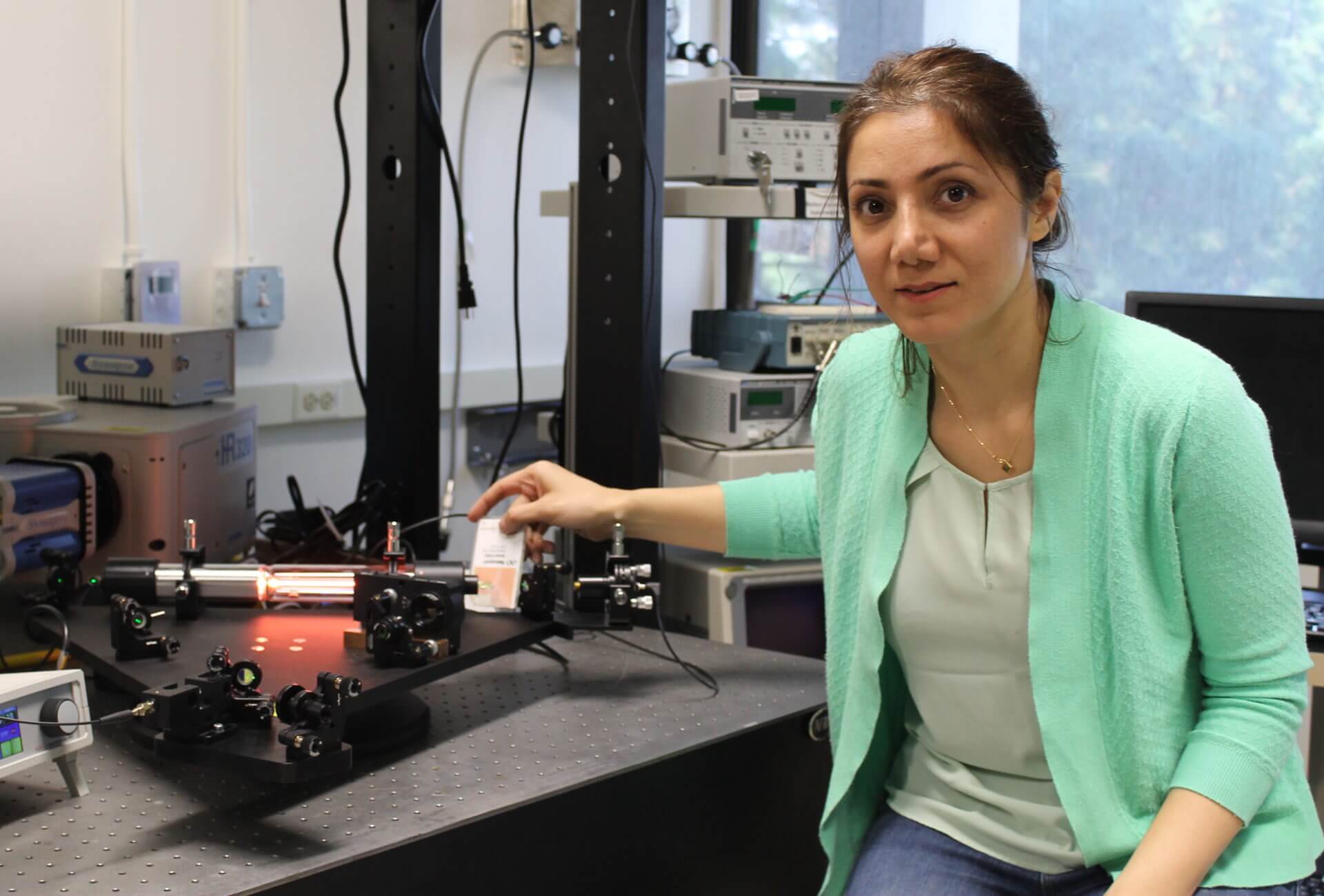

Professor Khajavikhan with her newly developed optical gyroscope (PHOTO CREDIT: USC Viterbi)

By using the newly developed concept of non-Hermitian exceptional points, Khajavikhan and her colleagues have successfully designed a special class of ring laser gyroscopes. Exceptional points are a special type of singularity that can be found in open or non-conservative systems. By designing a gyroscope that supports an exceptional point, Khajavikhan’s group has been able to beat the fundamental sensitivity barrier by more than an order of magnitude. Their calculations show that even larger enhancements are possible in future designs.

“We hope that our work will be used towards the demonstration of a new generation of small foot-print and batch fabricable on-chip ring laser gyroscopes that could be potentially used in a host of consumer, industrial, and tactical applications,” says Khajavikhan.

The next steps for her research are to work with Infinera, one of the leading companies in electro-optic technologies, to demonstrate the on-chip version of their free space-based gyroscope concept. If Khajavaikhan can perfect this technology, she predicts it could outperform our current state-of-the-art MEMS gyroscopes in terms of both sensitivity and size.

Published on January 23rd, 2020

Last updated on May 16th, 2024