Kandis Leslie Gilliard-AbdulAziz, Gabilan Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Imagine – an average day in LA, understood in terms of three prevalent products of consumption: corn, citrus, and bottled water.

For breakfast, you weigh up the options of corn syrup on pancakes, or (more advisable) perhaps toast with marmalade made with oranges from the tree in your garden. For lunch, you enjoy corn tortilla tacos from a food truck and – if you forgot your re-usable water bottle – you purchase a couple of plastic water bottles to hydrate in the heat. On your way home after work, you stop off at an elote stand to pick up a cup of hot grilled corn coated in mayo, melted cheese, chili and lime.

Another day, another trail of waste products: citrus peel, non-biodegradable plastic, and corn stover (the discarded husks and cuttings from corn harvesting, which amounts to the primary waste product in the U.S.). Add to the pile-up, all the carbon you burned while stuck in rush hour traffic.

Reframing waste

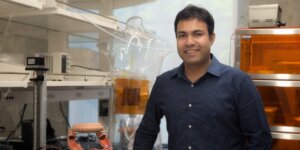

Where we might see waste, Kandis Leslie Gilliard-AbdulAziz sees potential. Having recently joined the USC Sonny Astani Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering as Gabilan Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Gilliard-AbdulAziz leads the Sustainable Catalysis and Materials Laboratory – a test site for transforming waste materials into unprecedented products which are beneficial for society. For her work in this realm, Gilliard-AbdulAziz was recently selected as a 2024 Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow in Chemistry, a distinction reserved for top early-career scientists from the United States and Canada.

Gilliard-AbdulAziz with waste accumulated after a typical lunch at the mall. Each waste type (plastic, paper, food) can be transformed into something valuable in the Sustainable Catalysis and Materials Laboratory

“The lab works within the field of catalysis for sustainable chemical production,” explains Gilliard-AbdulAziz. “We’re developing novel nanoscale activators that have the property of converting waste into use.”

“Essentially, we look at waste in two ways,” she continues. “At one level, we break down fairly large-scale polymeric materials – such as agricultural and plastic waste – into new and valuable products. In the past, my lab has worked on transforming corn stover and plastic waste into water filters or biochar; at the moment we’re experimenting with new opportunities for citrus peel, inspired by the prevalence of citrus here in California.”

“Then, zooming down to the atomic level, we study opportunities to use catalysis for the capture and sequestration of molecules such as carbon dioxide and methane, which can be extracted from the air and transformed into higher-value chemicals and potential sources of renewable energy.”

Working at different scales – from citrus peel to airborne atoms – Gilliard-AbdulAziz views her work as a way of boosting a circular economy for carbon, developing innovative processes of re-use that will be vital for mitigating global warming.

“Right now, we exist in a linear economy,” she explains. “We take, use and discard resources – it’s a one-way street. The technologies developed in my lab are intended to generate products that are inherently recyclable. As we see it, there’s no such thing as waste.”

The “aha moment”

For Gilliard-AbdulAziz, her “aha moment” came when she was working as a refinery chemist shortly after graduating. Given a tour of the facility, she learned that the plant was adjacent to a residential neighborhood.

“To be honest – sustainability wasn’t at the forefront of my mind before that point,” she admits. “But learning about the impact of the plant on the surrounding area was a turning point for me. It suddenly became clear that you couldn’t detach the chemical processes of industry from the social, systemic effects occurring on the ground.”

Her career then took a turn when she applied to be a forensic chemist for the Philadelphia Police Department, where her role involved analyzing illegal drugs. “That was a fascinating job,” she recalls. “I was right in the thick of things. If an officer suspected of someone of possessing heroin, cocaine, marijuana or any other street drug, they would ask me to test the confiscated materials – it was an incredible insight into what was really going on in the city below the surface, the narcotic use and trafficking that impacts peoples’ lives every day.”

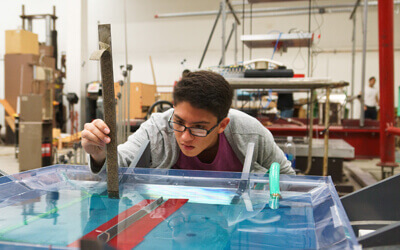

Biochar made from orange peels and seeds. This can be used as a soil remediation agent and can act as a carbon sequestration reservoir

After her experiences in the oil industry and the police force, it was clear that Gilliard-AbdulAziz was never going to be your average academic. When she decided to pursue a PhD in Chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, she also had her mind set on entrepreneurship.

“It’s important to me that discoveries made in the laboratory are also directly beneficial to society,” she explains. “The lab is just a conduit for innovations to enter the world at large, whether that

amounts to securing a patent or creating a business. My first experiment in entrepreneurship involved founding a company called Nardo Technology, which aimed to develop technology that would increase the accuracy of drug detection for police officers working out in the field. Running a business gave me a completely different perspective on how to generate and supply a product – it brought a new pragmatism to the way I approach problem solving, and ultimately to the way I work as a researcher.”

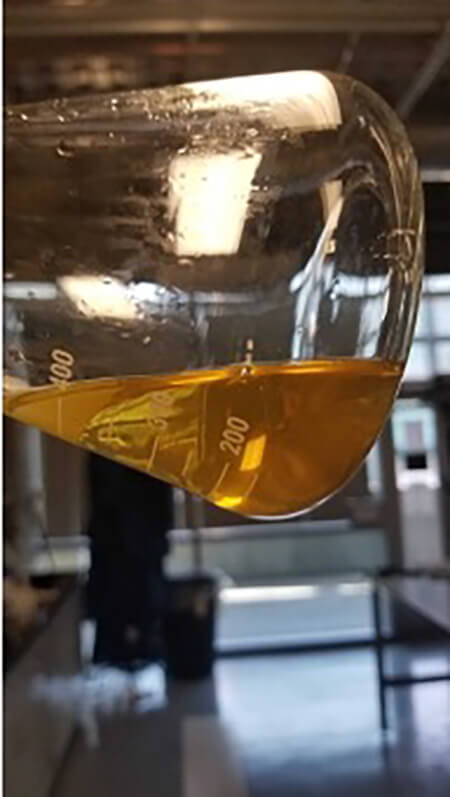

A flask of liquid extracts from oranges. The extracts can be used to derive bioactive compounds, gasoline and other chemical commodities

Catalytic reactions

Now that her academic journey has taken her to USC, Gilliard-AbdulAziz is excited about the prospects ahead. “It’s fantastic to have access to state-of-the-art facilities that significantly boost the quality of my lab’s research and output,” she says. “We’re able to tackle ever more complicated research questions, and the multiple specialist labs and centers mean that the opportunities for collaboration are immense. I’m particularly encouraged by the university-wide initiative Assignment Earth, which demonstrates the university’s commitment to fostering environmental sustainability.”

Gilliard-AbdulAziz is well aware that a mindset of sustainability takes work. Her own ecological consciousness was the product of unforgettable exposure to real human impact – a direct shock to the system. Addressing the climate crisis will require the same degree of awareness at the industry level, and that’s no small feat.

“Environmental sustainability sounds great, right?” she reflects. “We all know that we ‘should’ care about the health of the planet. However, how do we bring that into practice in the way we consume and the choices we make in daily life? My training in entrepreneurship has taught me to look to the bottom line when it comes to decision making, and it’s clear to me that expense is one of the major factors that dissuades industry leaders and policy makers from taking impactful action for sustainability.”

Natural empaths and business brains

Even as they’re deep in the process of catalysis, transforming chemicals and producing new nanomaterials, Gilliard-AbdulAziz and her team always have one eye on the external viability of the technology they’re developing. “We’re always asking ourselves – how can we streamline these processes to be economical as well as sustainable?

Assignment Earth is USC’s sustainability framework for creating a healthy, just and thriving campus and world

Do we, for instance, opt to use waste products instead of precious metals, do we extract value from readily available materials instead of rare resources?”

Speaking with Gilliard-AbdulAziz, it soon becomes clear that she’s guided by a business-brain as much as a natural instinct for empathy. A dynamic catalysis, it turns out, when it comes to addressing climate concerns. “It sounds tough, but we need a stronger value proposition for sustainability than the fact that it makes people feel good.”

That value, as it happens, can be found in citrus, plastic, corn – and many more products besides. So, the next time you squeeze a lemon and discard the peel, take a moment to consider the hidden chemical processes that have potential to turn the circular carbon economy.

Published on February 26th, 2024

Last updated on February 26th, 2024