Animals such as bears hibernate to survive harsh conditions. Yaoheng Yang is studying how hibernation could benefit human longevity. Image/Mike Boswell.

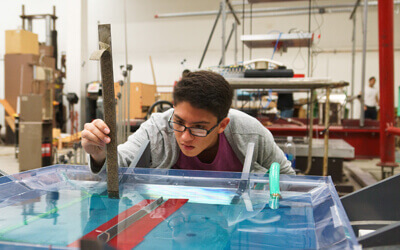

Yaoheng (Mack) Yang envisions a future where humans can live long, healthy lives, beyond the current limits of human lifespan.

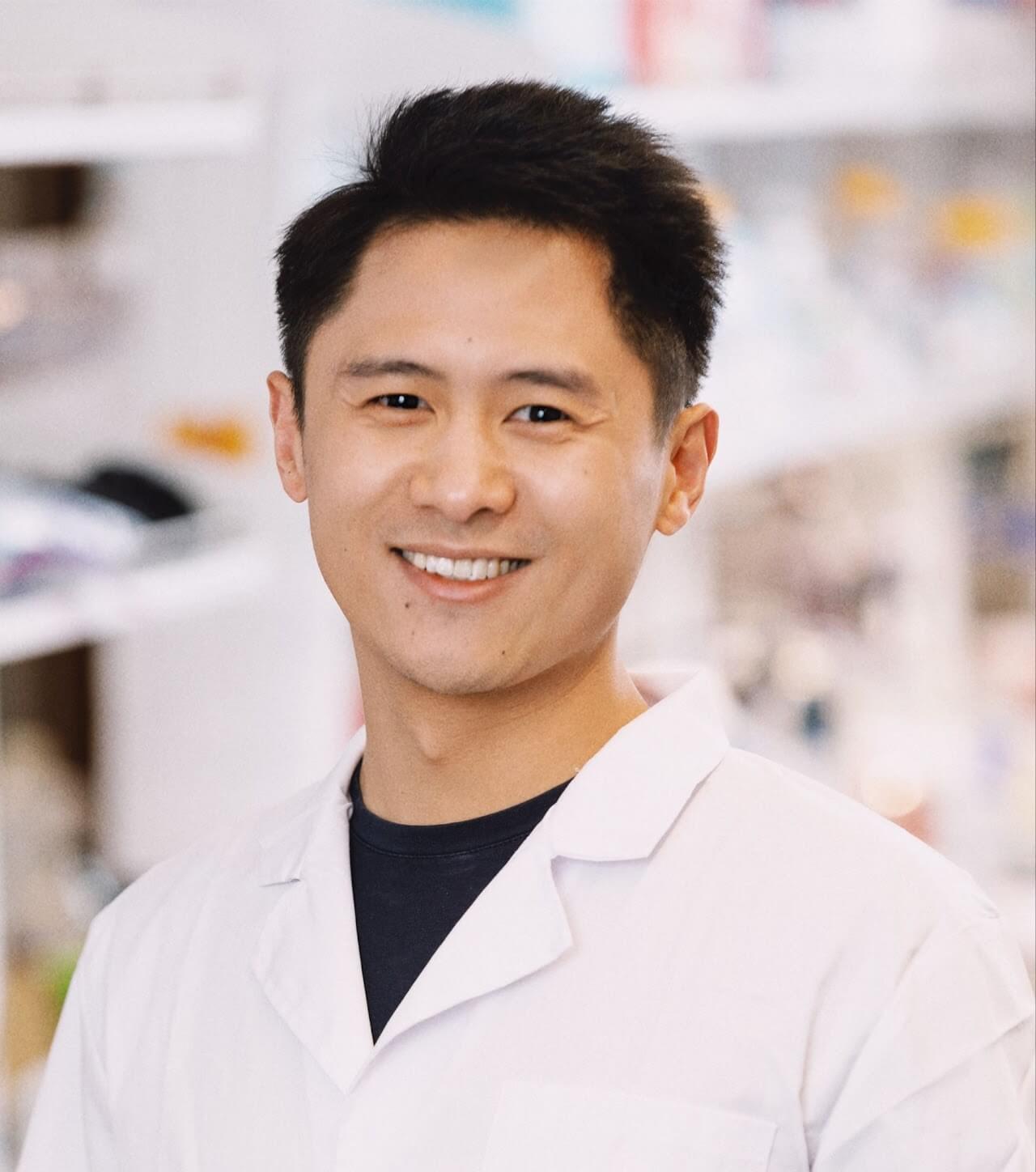

An expert in focused ultrasound for brain stimulation, Yang recently joined the Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering as an Assistant Professor. His lab’s research objective is to understand the aging process from a systemic perspective. Yang is particularly interested in the brain’s role in controlling how we age.

“We want to see whether we can develop any strategies that can slow down the aging process, not just for a specific aging-related disease, such as a neurodegenerative disease. We want to slow down the entire aging process,” Yang said.

For Yang, the key to unlocking the mysteries of human longevity could be found in a survival technique that is more common in the animal kingdom: hibernation. Many animals — from bears to groundhogs, frogs, and salamanders — have the ability to enter a state of suspended animation, sometimes for months at a time, allowing them to conserve energy and survive harsh conditions when food is scarce. During hibernation, an animal’s metabolism slows down, their heart rate and breathing decrease, and their body temperature drops to save energy.

However, hibernation is not currently a phenomenon seen in humans. For now, it remains in the realm of science fiction, such as in the Alien films, where astronauts enter induced suspended animation to enable long space journeys. As such, there are few studies on how humans could safely enter this state and what the potential benefits could be for longevity and fighting disease. The Yang lab hopes to change this.

“In the wild, animals go into hibernation, and researchers discovered that during the hibernation state, the biological aging process slows down significantly,” Yang said. “So that triggered us to see whether we can develop any technology that can artificially induce hibernation in animals that don’t usually go into hibernation, like humans.”

Studying the benefits of hibernation is particularly difficult, given it occurs exclusively in wild animals. Yang’s team’s solution is to explore ways to induce artificial hibernation in common laboratory animals that do not naturally hibernate, such as mice and rats.

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse in a state of torpor. Image/Rob Schorr, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Mice can go into something like a shortened hibernation; we call it torpor. But this usually happens in extreme cases,” Yang said. “So, our concept is that if we can induce artificial hibernation in the mouse or rat, it can be a research platform for us to study the benefit of hibernation. Whether there are any molecules or proteins induced by hibernation, and if these proteins can improve how the body repairs itself, so we can discover potential strategies to slow down the aging process.”

Yang and his team are pioneers in inducing the hibernation state without drugs or genetic modification, instead using a safe, non-invasive method — focused ultrasound, which is already a key research strength within the Mann Department. Focused ultrasound is currently being harnessed in the department by the Wang Lab for groundbreaking new cancer immunotherapy discoveries and by the Biomedical Ultrasound Lab (led by Zohrab A. Kaprielian Fellow in Engineering Qifa Zhou) for biomedical imaging and ultrasound-mediated therapies.

Yang said that using non-invasive ultrasound to stimulate the brain region known as the preoptic area (POA), the region that controls things like body temperature and sleep, can work as an on/off switch, activating a hibernation-like state, that was previously discovered.

“When we deliver the ultrasound energies specifically to that brain region, we find that animals can go to this hibernation-like state after receiving the ultrasound treatment,” Yang said.

Yang and his collaborators further explored the mechanism behind this by using single-cell sequencing to analyze the RNA and protein expressions in the POA region. Their pathway was to harness an ion channel called the Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) M2. This ion channel can sense the ultrasound signal that researchers targeted directly at the region and activate neurons that induce a hibernation-like state.

A “pause button” to enable more effective treatments in life-threatening situations.

Assistant professor of biomedical engineering Yaoheng (Mack) Yang.

There are many potential benefits of hibernation for human health, and Yang and his team hope to explore these possibilities.

“Hibernation is kind of like, a ‘buying time’ technology,” Yang said. “It’s something that enables you to press the pause button on the life process. By reducing the metabolic rate and reducing the body temperature we can slow down a lot of biological processes.”

“Imagine a patient who has a stroke or heart attack. In that moment the most important factor is time. You want the patient to receive treatment as fast as possible, which usually will not be the case,” Yang said. “But imagine if we could induce artificial hibernation to buy more time until the patient can receive treatment. We could save the life of someone who could otherwise die because of the narrow treatment window.”

Yang said that research had also shown that cancer progression slowed in animals during the hibernation period, a factor that potentially could be harnessed in the future to place patients in a hibernation-like state while they await the development of better therapeutics. A hibernation state is also potentially useful in radiation treatment, to avoid harming a patient’s healthy tissue.

Yang comes to USC Viterbi from Washington University in St. Louis, where he conducted research in Dr. Hong Chen’s lab and earned his Ph.D., receiving the Outstanding Doctoral Dissertation Award. Yang completed his Bachelor’s and M.Phil degrees at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and he has received a number of international awards, including the Nadine Barrie Smith Award.

The Yang Lab is now actively recruiting graduate and undergraduate students, with a focus on those with backgrounds in fundamental biology, neuroscience, electrical engineering and acoustic physics. Yang said that one of the most exciting parts of his work is the collaboration with colleagues and students, in particular the opportunity to mentor students as they work on new discoveries.

“Our lab is looking for students who are really passionate about fundamental questions, and who are also good at developing innovative technologies or tools,” Yang said.

For Yang, predicting how long the human lifespan could be extended to with the help of medical innovations and new therapeutic techniques is a complex question.

“My goal is to make human beings maintain health and vitality throughout aging, ultimately extending the limits of human lifespan,” he said. “You need to increase the healthy lifespan, making sure that people are still productive, and you still need to investigate new treatments or therapies for diseases like cancers, cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disease. Those are fundamental ways to improve healthy lifespan, and these efforts need to progress together.”

Published on March 12th, 2025

Last updated on March 28th, 2025