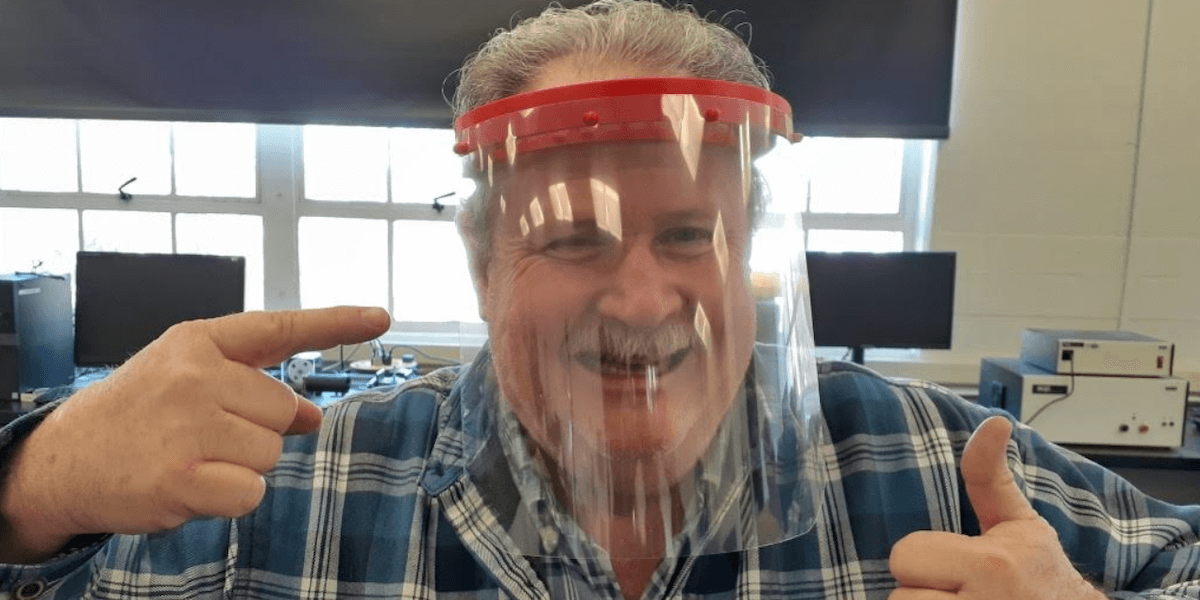

William Colvin, senior lab technician for the USC Viterbi Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering instructional lab, models a 3-D printed face shield. PHOTO/JEFFREY VARGAS.

A desperate national shortage of medical supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE) like face shields and N95 masks has already put healthcare providers in harm’s way, as they help battle the surge in COVID-19 cases from the front lines. Last week, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti shared an initiative to manufacture five million masks to help protect these workers.

At the University of Southern California, operations have largely moved remote, including research laboratories, which were closed temporarily in the wake of the city’s “Safer at Home” orders. At the same time, increasing demands for PPE for healthcare providers and other essential support staff from the Keck School of Medicine of USC and other local hospitals and clinics left researchers and designers wondering how they could help.

Charles Radovich, associate professor in the Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering (AME) and director of the AME instructional lab, and his team usually house their 3-D printer in Biegler Hall on the University Sciences Campus in downtown Los Angeles. Now fully remote, Radovich’s team met the call to action for more PPE with an out-of-the-box solution: recreating their lab at home.

“Our senior instructional lab technician Jeffrey Vargas took a 3-D printer home so that he could monitor production through the day without being on campus,” Radovich said.

The lab is producing 10 units per day, with enough materials to make 76 units at the moment. Each 3-D face shield costs a couple of a dollars to make. The teams have confirmed local hospitals will accept these shields, made of acetate and transparency sheets from office supply stores like Staples. All components for a face shield assembly are packaged into a Ziploc bag, which is then heat sealed to prevent contamination.

Radovich says they hope their masks will go to some of the smaller clinics or other “essential” businesses that might be left out of a more mainstream distribution. For now the goal is to acquire more materials, including two to three more 3-D printers, to speed up daily production.

Teams across USC Viterbi are mobilizing similarly to use whatever resources they can to meet needs on the front lines of the pandemic. Though 10 masks a day might not seem like much, the idea is that with all hands on deck, the community can have a larger impact.

Collaborating for Efficacy and Impact

In a virtual workshop hosted by Smith International Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Computer Science SK Gupta, Ray Irani Chair in Engineering and Materials Science and Professor of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science Andrea Armani and Professor of Industrial and Systems Engineering and Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering at USC Viterbi Yong Chen on Friday, April 3, over 60 researchers, engineers, designers and medical professionals from the USC community joined together to discuss how to best support medical facilities like Keck School of Medicine at USC through production of masks, ventilators and even swabs.

Said USC Viterbi Dean Yannis C. Yortsos, in his statement kicking off the workshop: “Our mission is to equip hospitals with PPE – equip doctors and nurses with the protection they need to respond to ill patients. We cannot underestimate the importance of this for everyone on the front lines. You cannot go to battle without equipment – and that’s really what this is. It’s very gratifying for us to see our teams step up in this effort and hopefully this workshop will be another way we connect to efforts in this area.”

Gupta – also director of the USC Viterbi Center for Advanced Manufacturing – said the virtual workshop was organized to ensure that work being done within the community to address PPE shortages and support colleagues in the medical field is effective and truly has an impact, from both a speed and a design perspective. Experts from Keck shared that even small discrepancies in designs could make healthcare providers vulnerable to potential exposure, so ensuring proper design and durable materials are used is an essential element in the manufacturing process.

Much of this work is being done ahead of a predicted “surge” in cases, though when this peak period will occur is dependent on how effective social distancing and other measures in place are in distributing spread over time. Kymberly Lengyel, associate administrator of infection prevention at Keck, shared estimates for current usage of disposable face shields equal 1,000 shields a day and that during a surge, this number could double. Reusable solutions would help bridge the gap in supplies, she said.

Traditional Manufacturing to Produce PPE

The Viterbi/Dornsife Machine Shop, which typically produces research equipment and scientific instrumentation to serve research projects through USC Viterbi and USC Dornsife, has shifted its focus to support university efforts in reducing the shortages of essential PPE among health care workers. Under the leadership of foreman Seth Wieman, the shop will produce protective face shields and eventually plans to also produce N95 respirator masks. N95 respirators are designed to provide an efficient barrier against small particles that can enter the body through the mouth or nose, and are worn under face shields, which are clear, plastic screens that cover the entire face to provide an additional barrier against airborne particles.

Although the machine shop has a few 3-D printers, it mainly contains traditional manufacturing equipment which will be used to produce PPE. Apart from requiring more initial setup time, the main difference between this more traditional process and 3-D printing is that it uses a “subtractive” process, meaning the team starts with a block of material and then whittles it down to its final shape, Wienman said. In 3-D printing, the process is “additive,” meaning material is added layer by layer to create the final product.

The equipment will be sent to Keck Medical Center for health care workers to use.

“I’m pleased that we’re able to adapt our work and resources to make a meaningful contribution,” Wieman said.

Coordinating Data Remotely

The mission to better arm those on the front lines is also being supported by USC Viterbi entrepreneurs and alumni. Stasis Labs, a five-year-old company founded by two USC Viterbi graduates, has offered its remote health-monitoring technologies to hospitals at a discount. The goal: reduce doctors’ and nurses’ exposure to patients with the coronavirus. Meanwhile, Atomus, a startup in the 3-D printer space headed by USC Viterbi students, has brought together the owners of 3-D printers and 3-D print file designers to produce protective face shields and other badly needed equipment for hospitals for free.

Stasis Labs manufactures a bedside technology that allows healthcare providers to remotely monitor patients’ six core vital signs: heart rate, blood oxygen levels, EKG, respiratory rates, blood pressure and temperature. Over the past five years, the company – a 2015 finalist in the Maseeh Entrepreneurship Prize Competition (MEPC) – has treated over 25,000 patients in India, its first market. The cloud-connected monitoring system, which recently received FDA clearance, has made it especially easy for healthcare providers to track patients living in remote areas.

When the pandemic broke, cofounders Michael Maylahn, B.S. BME ’15 and Dinesh Seemakurty B.S & M.S. BME ’15, had an idea: Why not make Stasis Labs systems available, at a reduced price, to overwhelmed hospitals, just as they are expanding capacity to treat surging numbers of Covid-19 patients?

The bedside system would allow doctors and nurses to remotely keep tabs on the health of scores of patients on a single cellphone, tablet or computer, freeing medical professionals to attend to more pressing matters than taking people’s blood pressure.

More important, Maylahn said, Stasis Labs’ remote monitoring systems would reduce medical personnel’s exposure to infected patients, keeping them safer during this pandemic. “We hope to save lives and help the frontline-care workers with this technology,” he said.

Atomus, a fledgling USC Viterbi startup, has developed a technology that allows defense contractors and others to license their 3-D design files directly to customers, making possible pay-per-print 3-D printing. Cofounded by Joel Joseph, a USC Viterbi undergraduate studying computer science, and Kaushal Saraf, a master’s computer science student, the firm has generated lots of excitement, landing contracts from the Marines and Air Force; winning the USC Hacking for Defense (H4D); and making the finals of this year’s MEPC contest.

In mid-March, Joseph began wondering what, if anything, he and Atomus could do to help others in this crisis. Then, it came to him. Given his and his team’s extensive contacts in the 3-D printing industry, Joseph and Saraf decided to create a website to bring together owners of 3-D printers, the designers of 3-D printer files and hospitals badly in need of lifesaving equipment.

“When you see an opportunity to help protect a life, you simply do everything you can,” Saraf said.

The company’s website now says: “Part of being a responsible company means stepping up when our community needs us. Our company has many military, commercial, and academic partners with 3-D printing and fabrication capacity who are willing to help respond to the current pandemic.”

Since launching the site, Joseph and Saraf have fielded dozens of calls and emails from 3-D manufacturers and designers offering their services and healthcare providers in need of them.

Through their tireless efforts, the Atomus executives recently matched dozens of 3-D printing firms with nearby medical centers in Pennsylvania and California. Using a customized 3-D file created by a network of designers, the manufacturers worked with Atomus to produce and donate over 1,000 face shields to grateful hospitals.

“There are 1,000 people who are maybe a little safer because of our efforts,” said Joseph, who said Atomus plans to continue its program. “The fact that we are able to make a difference is really, really meaningful to us.”

Since publication of this article, a contributing piece by Andrea Armani and colleagues regarding low-cost solutions to address COVID-19 was published in Nature.

Published on April 8th, 2020

Last updated on September 15th, 2021