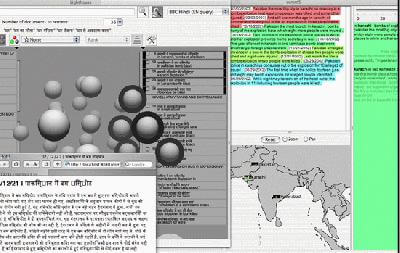

ISI search interface.

In less than a month, researchers at USC’s Information Sciences Institute and collaborators nationwide built one of the world’s best systems to translate Hindi text into English and query Hindi databases using English questions.

This effort was part of the “Surprise Language Project,” a test of the computer science community’s ability to create translation tools quickly for previously unresearched languages. Sponsored by the Defense Advance Research Project Agency (DARPA), the exercise ended July 1.”A month ago, we didn’t even know what language we would be working on,” explained Ulrich Germann, a computational linguist at ISI, which is part of the USC School of Engineering.

Then, at 10:55 p.m. PDT on June 1, the manager for DARPA’s TIDES (Translingual Information Detection, Extraction, and Summarization) program fired the starting gun with an email: “Surprise Language is Hindi…. Good luck!”

Teams at 11 different sites across the US and one in the UK jumped into action, and twenty-nine days later can present an impressive array of information processing tools for Hindi.

“We succeeded in all aspects of the exercise,” said Douglas W. Oard, an associate professor at the University of Maryland who is currently spending a sabbatical year at ISI. “A month ago, we had no information retrieval for Hindi, no machine translation, no named entity identification, no question answering. Now we have all of that.”

ISI’s researchers focused on four aspects of cross-lingual information processing: resource building, machine translation, summarization, and providing an efficient interface to navigate Hindi information space. Of these,”clearly, machine translation is the pivotal technology in this scenario,” said Germann.

ISI research scientist Franz Josef Och, a leading specialist in machine translation, did much of this key task for ISI.

“Our approach uses statistical models to find the most likely translation for a given input,” Och explained. “Instead of telling the computer how to translate, we let it figure it out by itself. First, we feed the system collection of parallel texts, material in the foreign language and their translations into English. The system tries to find the English sentence that is the most likely translation of the foreign input sentence, based on these statistical models.”

Och’s Hindi system was one of four developed independently during the exercise. Trials scheduled for coming weeks will rate his against those developed at other sites.

Finding and creating parallel texts for Och and his colleagues to analyze was a major effort during the exercise, said Germann. While for most European languages, there are one or two predominant standardized ways of encoding them, e.g.”Latin-1″ or Unicode, Hindi has a wildly mixed potpourri of encodings.

“It’s ridiculous,” said Germann, “almost every single Hindi language web site has its own encoding.” Tools had to be made to convert all of these various systems to a single common one to present parallel texts to Och and other machine translation experts.

“Most of the conversion work was done by our partners at other participating sites, and it was absolutely critical to the success of the exercise,” Germann said.

In addition to Och’s translation work, researchers applied search, summarization, and visualization tools developed at ISI to make Hindi texts more accessible to English language speakers. ISI researchers Anton Leuski and Chin-Yew Lin collaborated on a cross-lingual Google-like multi-document search, summarization, and translation system that allows users to enter search terms in English and generate results grouped by similarities found in the text. The system used and further developed a multi-document summarization technique developed by Lin.

Graduate student Liang Zhou developed a way to generate a headline for each group of similar stories found. Leuski’s unique Lighthouse visualization system displayed these results at spheres floating in groupings on the screen, with the most similar closest together.

The bottom line: a user can view individual documents, or automatically generated summaries for whole groups of documents. Even though all documents were originally in Hindi, all the added value is available in English, thanks to the machine translation engine. In addition, references to geographical locations in the documents are spotted (using a third-party tool, the BBN IdentiFinder) in the text and plotted on a map.

“It’s just wonderful to see so many of the technologies that we have developed at ISI come together and interact in such a useful way,” said Eduard Hovy, head of ISI’s Natural Language Group.

Multi-document visualization tool searches, returns and groups documents starting with English search terms.

In addition to USC/ISI, other participating institutions included the University of Maryland, College Park, the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Laboratory, Carnegie-Mellon University; the University of California, Berkeley; New York University; the University of Massachussetts, Amherst; Johns Hopkins University; the University of Pennsylvania; the University of Sheffield (U.K.), the MITRE Corporation, BBN Technologies, and the Navy Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR).

Published on June 30th, 2003

Last updated on June 11th, 2024