View of the Glendale Narrows section of the the Los Angeles River

Take a stroll along the section of the LA River that runs through the Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Frogtown and you’ll encounter cyclists, dog walkers, birdwatchers and the occasional artist. With its islands of mature trees and dense vegetation, this is one of the more scenic turns in the much-maligned river – give or take an abandoned shopping cart or two.

In recent years, the area – referred to by environmental planners as the “Glendale Narrows” – has also been a point of pilgrimage for researchers and students in USC School of Architecture, USC Viterbi School of Engineering and USC Cinematic Arts. Led by landscape architect and associate professor Alexander Robinson, the team has designed and built a 1:120 scale hydraulic model of the Glendale Narrows, housed in the City of Los Angeles’s Hydraulic Research Laboratory. The model is designed to support the research and community engagement goals of the Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan, one of the nation’s most technically complex urban flood control projects, and is made possible with the support of City of LA Bureau of Engineering, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the USC Office of the Provost, USC Dornsife Public Exchange, Metabolic Studio, and grant funding from organizations including the National Endowment for the Arts.

Poetry and pragmatism

Mitul Luhar, Gale Lucas and focus group participants experiment with pick-and-place vegetation to create different flow patterns

Too often dismissed as a stark concrete channel, the LA River is now being reimagined as an evolving source of vitality for the city, both culturally and ecologically, with a correspondingly ambitious social agenda.

That said, the revitalization has been decades in the making, slowed by a tension between aspiration and practicality. Utopian visions that seek to pull up the concrete and restore the river to its original alluvial glory – remember the days of Los Angeles as an agricultural paradise – overlook the complex hydraulic conditions, associated flood risks and the unpredictable factors of climate change. Meanwhile, top-down strategies to protect people and property from flooding have historically overlooked the lived experience of the local communities who live in proximity to the river.

The model is designed to bridge this divide. “We need a new approach that engages civic imagination in a meaningful dialogue with the river’s complex engineering functions,” said Robinson. “It was clear to me that this project would need to be highly interdisciplinary, prototyping a flexible and impactful landscape design methodology that could serve as a precedent for sustainable flood control practices going forward.”

Accuracy and interactivity

Robinson’s team of students and landscape architects – the LA River Integrated Design Lab – aim to develop different design scenarios for the river channel that take into account the complex flow conditions while integrating the visions, needs and expertise of numerous stakeholders; from ecologists and environmental scientists, to community activists and local residents.

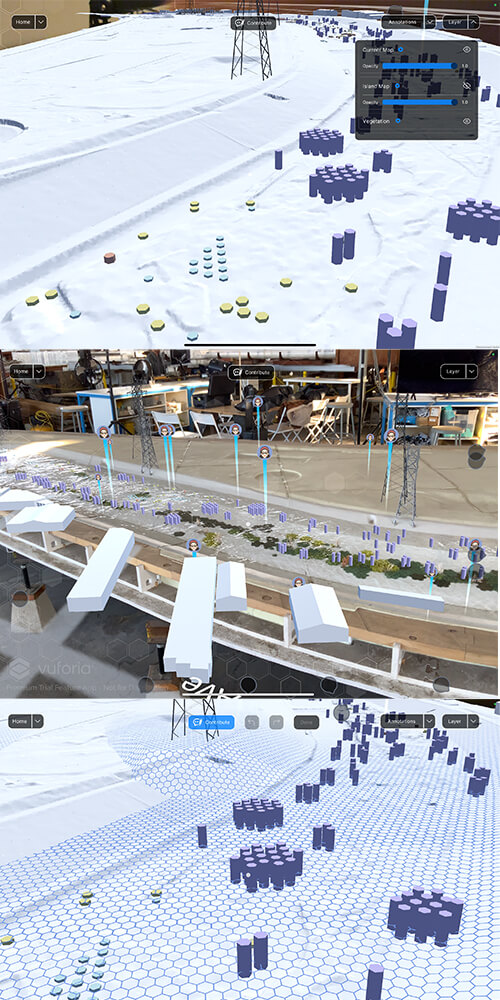

AR application overlay on the physical model of the LA-River section, developed by a team at USC School of Cinematic Arts.

To achieve this, Robinson reached out to Mitul Luhar, Henry Salvatori Early Career Chair and associate professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering and civil and environmental engineering, and Andreas Kratky, associate professor of cinematic arts and associate dean of research, to create a technologically innovative model that would maximize opportunities for accessible and inspiring interaction. USC Public Exchange led a recently completed pilot to test the efficacy of this tool in improving the public’s understanding and bringing the community into the design process.

Working with student researchers in the Fluid-Structure Interactions Lab, Luhar has engineered a carefully scaled and structured physical simulation of the river channel that replicates potential flooding outcomes when running water is passed through at fluctuating rate and volume.

“Fluid dynamics involves the study of the motion of air, water and other fluids, and how factors such as the roughness or porosity of a surface impact flow,” Luhar explained. “Working on the project has allowed my team to see how fundamental research topics studied in the lab can directly impact our community.”

“In designing the model, we’re asking – what water depths do we need to replicate different flood conditions? What kinds of flow rates? Do we need a specific type of gravel or stone bed, and how might we represent the different vegetation (whether native plant species, tree species or invasives) by appropriately scaling the geometric parameters that affect flow resistance and water diversion?”

Fluidity and flexibility

Adjustable elements such as 3D printed magnetic “pick-and-place” silicon vegetation and a modular structure allow for flexibility when experimenting with different design approaches, and Luhar’s team have installed a camera system above the model for data tracking via image analysis algorithms. This data also feeds into the digital dimension of the model developed by Kratky and his team of students specializing in AR and interactive digital media. By pointing an iPad at the model, new layers of graphics and information are revealed, further enhancing accessibility of interaction and the possibility for anyone to play the role of designer.

The scope of those layers of information and the different pathways for digital engagement are currently being tested with focus groups, including those facilitated by Gale Lucas, research assistant professor of computer science and civil and environmental engineering. Her work at USC Viterbi Institute of Creative Technologies specializes in human-computer interaction, affective computing and trust-in-automation. The design team is currently trialing a version where participants can use the AR interface to tap into training modules about the history of the LA River and the hydrodynamic challenges, as well as annotating design proposals by adding text, drawing simple structural elements and adding vegetation.

“The goal is for the AR component to empower users of any background to play out different design scenarios, and to input their ideas into the discussion about the future of the river,” explained Kratky. “Through the sessions with different participants, we’ll build a database of ideas, interventions, commentary and criticism that will be aggregated over time – ultimately serving as a historic trace of how and why certain solutions were reached.”

The dao of design

Those design solutions – the as yet invisible blueprint for the future river – are still years in the making. In the meantime, the model will be manipulated, digital innovations updated and community members consulted. Another element in the works is the construction of The Los Angeles River Observatory; a collaboration with Josh West, professor of earth sciences and environmental studies, and Isaac Brown, senior scientist at Stillwater Sciences and lecturer at USC School of Ar

AR application overlay on the physical model of the LA-River section, developed by a team at USC School of Cinematic Arts.

chitecture. With funding from the USC Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability, the observatory will enable data gathering of real-time flow patterns, track water depth and temperature, and monitor wildlife.

By revealing the layers of information embedded within urban ecologies and infrastructure, the project as a whole serves to enrich that quality of “civic imagination”; the capacity to think boldly and creatively about how to live collectively and in relation to the natural world. By taking the time to pause and observe, every corner of the city is revealed to be rich with a constant influx of data. Just as AR can cultivate curiosity and engagement with our surroundings, design and engineering can reveal our shared role as technological problem solvers and civic participants.

For Robinson, the development of an interdisciplinary design process that is “imaginative, inclusive and technically informed” has the potential not only to generate applicable design scenarios for the city, but also to significantly advance academic scholarship in engineering, landscape architecture, mixed reality and community engagement. Years of studying and working alongside water has also given him a keen awareness of where design ends and nature takes over. “These simulations can’t tell us exactly what the river is going to do,” he reflects. “Only the river can tell us that.”

Published on February 9th, 2024

Last updated on February 23rd, 2024