(ART/SHUTIANYI LI)

This fall, following the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) Call to Action for engineers to “crowdsource and collectively brainstorm engineering solutions for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19),” the USC Viterbi School of Engineering is offering “Viterbi vs. Pandemics!” — a new lecture series by USC Viterbi faculty to comprehensively provide an engineering-centric framework for addressing and understanding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cyrus Shahabi, chair of Department of Computer Science

During the 11-week, free program, students gain exposure to myriad topics, ranging from the estimation of risk and protein engineering by directed evolution to the contributions made by computer science and electrical engineering faculty in automating human safety technologies, detecting misinformation and digital contact tracing. The one- to two-hour sessions take place on Thursdays at 6 p.m.

On Nov. 5, Cyrus Shahabi, the Helen N. and Emmett H. Jones Professor of Engineering and professor of computer science, electrical engineering and spatial sciences, presented his lecture: “Digital Contact Tracing.”

Shahabi, the chair of the Department of Computer Science, discussed the various approaches to collect people’s mobility and contact patterns for various contact tracing and risk estimation applications.

For those who missed it, can you briefly summarize your lecture for a general audience?

Digital contact-tracing, along with testing, is pretty much the only solution offered to gradually relax stay-at-home orders, allowing us to get back to work and normal life.

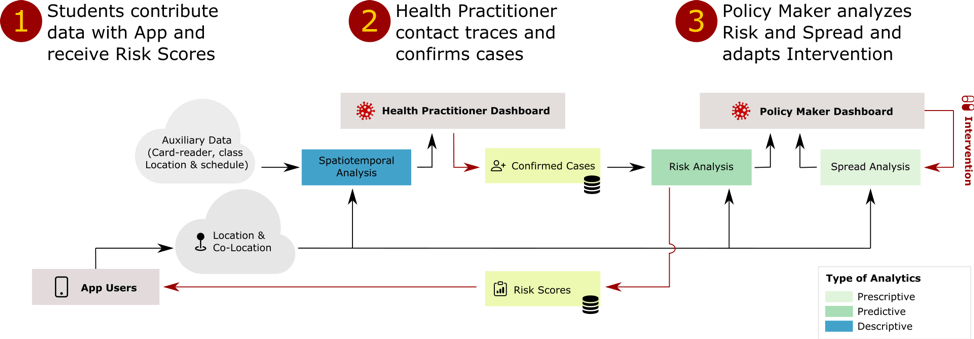

A recent effort by Apple and Google to collect co-location data, which would enable large-scale contact-tracing in real-time using Bluetooth-based proximity detection, is a step at the right direction. However, in this lecture, we discussed the limitations of the Bluetooth-only approach and the advantages of also collecting location traces in a privacy-preserving manner. We then presented our holistic platform, called Pandemic Risk Evaluation Platform (PREP), which includes contact mapping and risk analysis that are complementary to any contact-tracing app. We then demonstrated the current state of some of the PREP’s components, including our contact-tracing app and dashboard (for health practitioners) and density mapping dashboard (for policy makers). Finally, we discussed some of the research challenges underlying the PREP platform for risk score computation and privacy-preserving data collection and presented our approaches to address these challenges.

Why is this research important? How will it help in the fight against COVID?

As countries look towards re-opening economic activities amidst the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, ensuring public safety has been challenging. While contact tracing only aims to track past activities of infected users, one path to safe reopening is to develop reliable spatiotemporal risk scores to indicate the disease’s propensity. Thus, as the number of cases reach record levels, and a general sense of pandemic fatigue sets in, it has become important to develop practical tools for navigating the disease safely to resume normal activities. PREP is a holistic platform to not only enable digital contact tracing, but also allow for assigning risk scores for different regions and individuals to show the danger in each area for each person. This can be used both for policy making at the government level as well as individual decision making (e.g. to avoid high-risk areas or to get tested if individual risk is high).

How would you compare your research to similar research or ideas, either in academia or industry?

Our digital contact tracing approach goes beyond the mobile phone apps proposed by academia and industry — the most popular of which is a recent effort by Apple and Google to collect co-location data.

While these approaches would enable large-scale contact-tracing in real-time using Bluetooth-based proximity detection, they still have several limitations. First and foremost, due to the relatively wide-range reach of Bluetooth devices — including signal penetration through walls, ceilings and floors — this approach would result in many false positives. You’re unlikely to be directly infected by someone who you never meet face-to-face, but your phone won’t know this using Bluetooth alone.

We need more data (for instance, your social relationship to someone, inferred from previous frequent encounters) to determine who you have directly come into contact with, versus someone who just happens to be in the next hotel room, for instance. In addition, by design, the proposed approach would alert anyone who has been in contact with a confirmed case, including these false positives. This method may be effective now, while we are all at home, but as soon as we all go back to work and school, we may each receive several alerts per day, to the point that we turn numb to them. We witnessed the same effect in the past with car theft alarms and tornado and storm warnings in some parts of the country, with disastrous consequences. In the lecture, we discussed other differences in detail.

What are the next steps and/or milestones in terms of your work?

While location-based risk scores can be used to control re-opening, our future works entails developing individual-level user-specific risk scores. One way to accomplish this is by combining user trajectory prediction models with our spatiotemporal risk prediction model. Any user-level risk prediction model will also involve reconciling the associated privacy issues. Finally, we would like to use our spread simulator, which uses real-world, check-in data to generate infection patterns, to study various intervention policies. For example, to study how much the rate of infection is reduced if individuals with high risk scores (say, higher than 0.8) self-quarantine or locations (e.g. a shopping center or restaurant) with high risk scores stop admitting new customers.

Tell us about your collaborators. What unique skills does each person bring? Are you partnering with any doctors, clinicians or other non-engineers in this work?

The main team in charge of developing various components of PREP is led by my research staff: Dr. Luciano Nocera, working with three of my Ph.D. students, Sepanta Zeighami, Kien Nguyen and Ritesh Ahuja; one M.S. student, Sitao Min; and three undergraduate students, Kameron Shahabi, Yingzhe (Nikki) Liu and Abbas Zaidi.

In the design and development of PREP, we worked with a large number of colleagues from different disciplines and across different universities. Our project is partially funded by an NSF RAPID grant. For this grant, we assembled a multidisciplinary team from three institutes:

- Emory University

- Li Xiong (CS and Biomedical Informatics)

- Vicki Hertzberg (Nursing)

- Lance Waller (Public Health)

- University of Southern California

- Cyrus Shahabi (CS, ECE, and Spatial Sciences)

- University of Texas, Health Science Center

- Xiaoqian Jiang (Biomedical Informatics)

- Amy Franklin (Biomedical Informatics)

We have also worked very closely with a contact-tracing subcommittee at USC, led by Professor Maja Matarić, USC’s vice president of research, which included colleagues from several schools, including Dr. Sarah Van Orman, USC’s associate vice provost for student health; Bob Gross, USC’s director of data privacy; and Douglas Shook, USC’s chief information officer. Our USC density map is being developed in collaboration with USC ITS. Finally, an early version of our contact tracing app was developed in collaboration with Professor Peter Kuhn, Dean’s Professor of Biological Sciences, and his team. And for our risk score analysis, we collaborate with Professor Yan Liu and her postdoc, Dr. Sirisha Rambhatla.

I think a system as critical as PREP can only make real-world impact if it is designed and developed with all stakeholders involved. That is why in every step of the PREP’s design and development, we involved this amazing team of collaborators.

Can you share one story from your pandemic life? How has it impacted your work and family? What are you doing to stay sane?

We had water damage in our house in late March, and because of the pandemic, we couldn’t leave the house. So, we ended up staying in the house while it was demolished and restored over the course of two months. We also eventually purchased another property and moved, as well as sold the old house, all during the pandemic.

This took a major toll on me and my family, but at the end, things worked out fine. I used to travel a lot for work and didn’t realize how much this helped me in taking a break from the day to day work. Without the traveling and also without going to campus to hang out with students and colleagues, I am realizing that the best part of my job is gone. Thus, I am really looking forward to getting back to normal life. That said, I am thankful that I still have a job and my family are healthy and well. To stay sane, I exercise: jogging, yoga, stretch and weights, averaging at least 30 minutes per day. I also go for walks with friends at least once or twice a week.

From a research perspective, what do you consider the most surprising or counter intuitive aspect of the virus or the pandemic as a whole?

What surprised me was how little we knew about the virus, how it spreads and its impact on humans early on and how long it is taking us to learn about these.

We still do not know why some people are affected so severely and some don’t even show any symptoms. We also don’t know how long someone is immune for after getting the disease. I was also surprised that people are willing to share location information and trust companies to track our location all the time — whether to shave a few minutes off our commute or receive a coupon for our next Starbucks stop — but do not trust these companies with our location data to stop a pandemic. Why not put to work technology, which we as consumers already use for convenience, to save lives?

What are some words of wisdom regarding the pandemic that have meant a lot to you?

I believe during the time of pandemic, the following poem from the Persian poet, Sa’adi, is very relevant:

“Human beings are members of a whole, in creation of one essence and soul. If one member is afflicted with pain, other members uneasy will remain. If you have no sympathy for human pain, the name of human you cannot retain.”

If you could only share one slide from your talk, what would it be and why?

PREP: Pandemic Risk Evaluation Platform

This slide summarizes our PREP approach to contact-tracing. It shows that our approach is beyond a simple app: it is a holistic approach, which includes contact mapping and risk analysis that are complementary to any contact-tracing app.

Published on November 13th, 2020

Last updated on May 16th, 2024