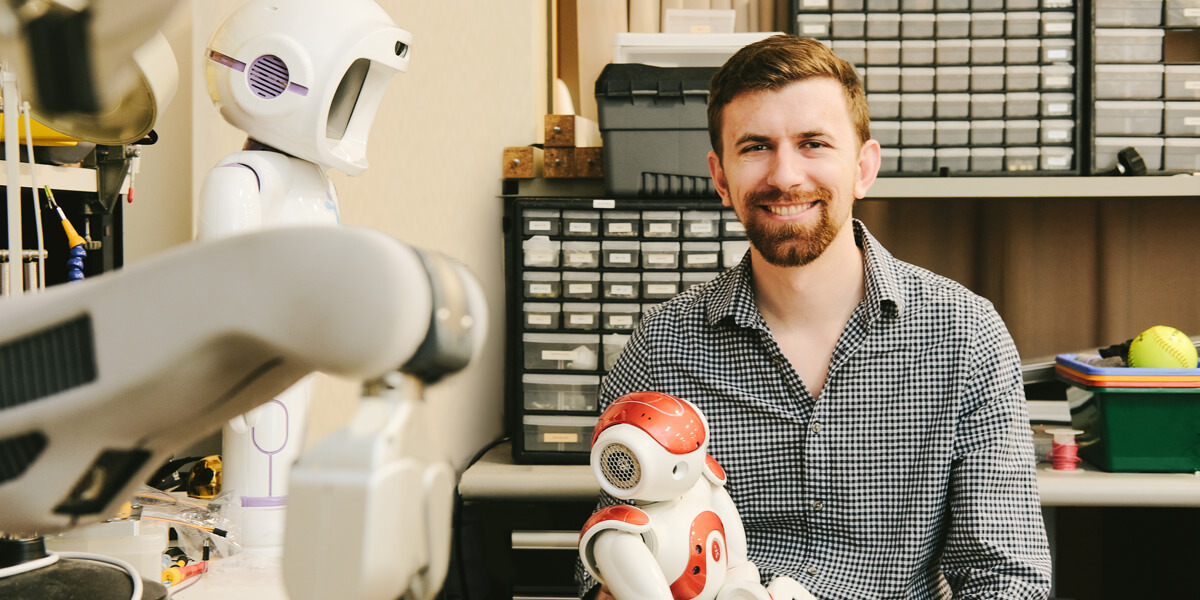

Chris Birmingham is developing robotic technologies to support people coping with difficult health conditions, such as cancer. Photo/Keith Wang.

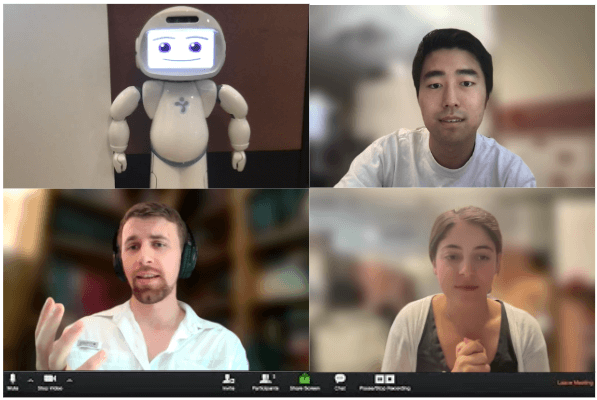

It’s a winter’s day in 2022, two years into the coronavirus pandemic, when three people, all cancer survivors, gather on a Zoom call. The occasion is a group therapy session and they have come together to share their experiences and provide support.

Then, a special guest joins the room. A small humanoid robot called QT. The session gets underway. “Some days it feels like all I can think about is the possibility of the cancer coming back or not responding to treatment,” says one of the participants, a 33-year-old man from Irvine, California.

After a brief pause, QT responds. “I hear you. It sounds like you are experiencing a real and valid fear. Thank you for sharing with us. Can anyone else relate to what was just shared?”

Sitting behind the robot, just out of frame, is Chris Birmingham. Birmingham, a computer science PhD student who graduates May 10th, has been training QT for the past two years. By now, after years of modeling and training, the robot is mostly autonomous, interacting with participants in an authentic way—a huge breakthrough.

But for Birmingham, this is more than just research—it’s personal. Less than a year ago, Birmingham was also fighting a recurrence of melanoma, a serious form of skin cancer.

He was first diagnosed in the summer of 2015 shortly after completing his undergraduate degree and was preparing to move to Bristol, England, to complete his master’s when the diagnosis halted his plans.

“I was being treated during what would have been my first semester in Bristol,” said Birmingham. “The most succinct way to describe a diagnosis like that is that it kind of knocks you off kilter. I felt like I was standing upright, but the whole world had shifted. And now I was standing on a hill about to fall down.”

Undergoing numerous surgeries and treatments, Birmingham felt frustrated and alone. He wanted to help people like him, and he wanted to help them now—not 10 or 15 years down the line.

“The experience cemented the urgency of helping people,” said Birmingham. “I had a pressing need to do something now, in the short term. That really sparked my interest in building social robots or socially assistive robots that could help people.”

After completing his master’s at the University of Bristol, with the cancer in remission, he returned to the U.S. to build future connections in the field and be closer to his girlfriend, now wife. That’s when he happened upon Professor Maja Matarić’s Interaction Lab at USC. Their missions aligned.

“It was one of the only groups I had found that was taking robots and putting them in people’s homes, putting them in people’s lives, and evaluating how that actually makes a difference,” said Birmingham.

Bringing people together

Birmingham’s research focus was initially born out of his own struggle with isolation in online spaces. During the first year after his initial diagnosis, said Birmingham, he had a lot of time with nothing to do.

“It was particularly challenging because having just graduated from college, all of my peers had just shot out into the world, and everybody was living their lives, and I was kind of stuck in stasis,” said Birmingham.

What if, thought Birmingham, we could create technology that brings people together to interact with one another as opposed to isolating people? A support group—where people come together to share common experiences and offer practical advice—seemed like the perfect environment to see how robot behavior influences social dynamics overall.

Birmingham and his labmates model how cancer survivors interacted with the QT robot through Zoom in an online cancer support group.

“The application domain that I chose is very close to my heart, because support groups have been really important in helping me to get through my cancer experience,” said Birmingham. “In a support group you experience a very fast and deep connection with other people. So having a robot that can learn from that kind of environment is really instructive.”

The aim of his research, said Birmingham, is not to replace therapeutic facilitators. Instead, it is a learning exercise to better understand how a robot in the world can interact with groups in positive, healthy and constructive ways.

“My goal is not to build a facilitator robot that’s going to be a product or going to facilitate support groups,” said Birmingham. “It’s really to learn how a robot should interact with a group of people to support healthy relationships.”

Responding with empathy

In one early experiment, Birmingham worked with students in an academic stress support group. USC students came into the lab before finals in groups of three and sat around the table talking to each other—and a humanoid robot called Nao. From that data, Birmingham started to build models of the interactions and train the robot to produce appropriate responses.

Birmingham was particularly interested in how people support each other in therapy groups. So, he zeroed in on “disclosures”—statements about something that happened or how someone is feeling—which people in a support group respond to, usually with empathy.

“There’s the element of unburdening yourself or disclosing and sharing with the group, and then people responding with empathy or with advice,” said Birmingham.

“I trained the robot to recognize when people are making disclosures and built a model of how the robot can respond empathetically or convey that it understands that it hears what somebody is saying.”

A later study lead-authored by Birmingham, which specifically looked at ways that robots can respond empathetically, found two main types of empathy: cognitive empathy and affective empathy.

“Cognitive empathy is where you show that you understand what somebody is telling you,” said Birmingham. “Affective empathy is more about expressing that you’ve experienced it before, and you really get it.”

He found that people preferred affective empathy from a robot (“I’m sorry you’re experiencing this”) as opposed to cognitive empathy (“I’ve experienced this before”). He also found that attitudes towards robots in general influenced which kind of empathy people preferred in this context.

“People with more negative attitudes towards robots, in general, are more likely to prefer cognitive empathy,” said Birmingham. “Whereas people who thought that robots are great, and fun are more likely to anthropomorphize and believe the affective empathy over the cognitive empathy.”

Courage, determination and grit

In 2020, life and research were going well for Birmingham. He received the USC Robotics Lab George Bekey Service Award for his contributions to USC’s robotics research community and got the all-clear during his five-year cancer checkup.

But the following year, as he was making strides in his research, and a week before his dissertation proposal, Birmingham was dealt another health blow. The cancer was back.

Birmingham was forced to take time off from his PhD to begin treatment, and during this time, married his wife, who he had met during freshman year of their undergraduate degree.

“Chris displayed tremendous courage, determination, and grit,” said his supervisor Maja Matarić. “All the while, he aimed to return to the PhD program and finish his degree, and while we all worried, his courage and strength gave us all confidence that he would.”

And he did. After eight months, Birmingham resumed his studies in the summer of 2022, first part-time, then full-time, and dove into collecting data from robot-supported cancer sessions with patients like himself.

“We had gone from the beginning, where I was controlling the robot so that the robot could learn, to at the end of my PhD where the robot was mostly controlling itself,” said Birmingham.

This research produced the first results of what is now a National Science Foundation-funded grant, which will allow the lab to expand upon Birmingham’s work in the future. Now, approaching graduation, Birmingham hopes to parlay his expertise into a burgeoning area of research: mental health chatbots.

“You can always talk to a chatbot, any time, any day. Having that support there, I think it’s really beneficial. I have actually used some of these apps and found them to be helpful myself,” said Birmingham.

“I would love to take some of my experience around making the interaction more multimodal, instead of just a text conversation, to make these chatbots into something that people can really benefit from.”

Despite being a lifelong roboticist, for Birmingham, people are the heart of everything. From his wife, who is now a doctor, to the cancer support group community that inspired his research in the first place, to his peers and professors at USC.

“The people that I’ve met at USC have all been really smart, passionate, wonderful, driven people and being in that environment definitely helped push me to do the best that I can in my research,” said Birmingham.

The feeling is mutual, said Matarić.

“It has been a joy to have Chris as a student, and I can’t wait to see what his next life step will be,” she said. “I know he will strive to do the very best to help others and make a meaningful impact. He is a role model and makes us all proud.”

Published on May 8th, 2023

Last updated on May 16th, 2024