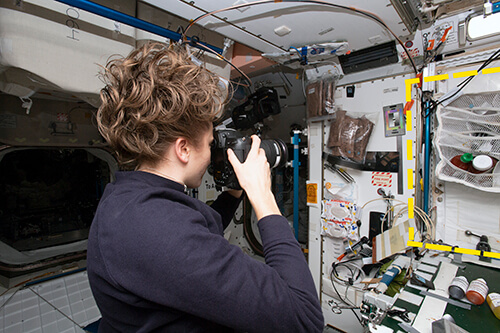

NASA astronaut Kayla Barron photographs sample location in the US Node 1 module in the International Space Station, for the SQuARE experiment @NASA/International Space Station Archaeological Project

So far, the adventures of Indiana Jones haven’t led him to the study of space. That’s where Justin Walsh, Ad Astra Fellow at the USC Space Engineering Research Center (SERC) is a step ahead of Hollywood’s best-known professor of archaeology.

Walsh is professor of art history, archaeology and space studies at Chapman University, where he splits his time between archaeological excavations of an Iberian indigenous settlement in Andalusia, and the meticulous analysis of photographs captured on board the International Space Station (ISS).

ISSAP logo. @Sarit Ashkenazi/Cameron Mannen/International Space Station Archaeological Project

Together with Alice Gorman, a professor at Flinders University in South Australia, Walsh is Co-PI of the International Space Station Archaeological Project (ISSAP): the first archaeological “excavation” of a space habitat and the ideal controlled study of the effects of microgravity on human behavior and social relations.

Why is this study so important for the future of space travel?

“Engineers tend to think of logic and manual work as the primary drivers for human-rated space systems,” admitted David Barnhart, USC Viterbi research professor of astronautics and director of SERC. “However, that mindset risks overlooking the vital human elements involved in off-planet living and potential long-term settlement. By viewing life on the ISS through the lens of archaeology and anthropology, Dr. Walsh is revealing new, human-centered insights that might surprise the original planners of the ISS.”

First launched in 2015, the ISSAP project has involved data collection and machine learning analysis of historical photos as well as proprietary records of objects traveling to and from the ISS. Now, the preliminary findings of the team’s first in-orbit fieldwork experiment have been shared at USC during a presentation in September 2023 by Walsh as part of his fellowship with SERC.

From shovel to SQuARE

So far, there isn’t scope for an in-house archaeologist aboard the ISS. No matter. The beauty of this type of research is that it can be conducted remotely, through the analysis of photographs captured by astronauts. The method developed by Gorman and Walsh, the Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment (or SQuARE), takes inspiration from one of the most basic archaeological techniques for sampling a site: the shovel test pit.

When embarking on an earthbound excavation, the shovel test involves laying out a grid of one-meter squares; contained areas of focus that help to inform the strategy for the site as a whole.

“Our take on this method was to mark one-meter squares on various walls of the ISS with yellow tape, and have the crew photograph them at the same time every day for 30 days, then at random times for another 30 days,” explained Walsh. “You can think of it as an off-planetary equivalent of excavating a pit.”

The dotted yellow line outlines the sample location for SQuARE @NASA/International Space Station Archaeological Project

This new approach to archaeology has important implications for the discipline as a whole, demonstrating new possibilities for in-depth study of comparatively inaccessible and high-risk locations. Walsh reflected on the experience of watching a livestream of NASA astronaut Kayla Barron capturing the first photos of the grid.

“It’s hard to describe the feeling of watching something happen for the first time in your discipline,” he said. “In this case, an astronaut floating in microgravity and doing archaeology on a spacecraft traveling 17,000 miles an hour at an altitude of 250 miles over the Earth.”

With the assistance of Salma Abdullah ’23, a USC graduate in archaeology, Walsh and his team are in the process of tagging the objects that appear in the photographs – that tagging process will build the machine learning dataset for analyzing trends and discrepancies. So far, the team has two squares completed – and while this may not seem like a lot, Walsh’s presentation revealed the unexpected insights that can be gleaned about how spaces and resources are actually used.

Maintenance and cake frosting in microgravity

The emphasis on the actual – as opposed to the potential or imagined – is a recurring concern for Walsh. All too often, the way we interact with an environment differs from the original design intentions, and our faulty memories further obscure the truth.

The documentation of one square of a maintenance workstation is a case in point. The analysis indicated that the designated workstation was predominantly used for storage rather than actual maintenance – “the equivalent,” Walsh quipped, “of a pegboard in someone’s garage.” Furthermore, within the same square, 35% of artifacts were in the category of restraints for holding other items in place – so-called “gravity surrogates” such as clips, bungee cords, adhesive tape and cable ties. This compared to only 12% for maintenance tools.

SQuARE logo @cheatlines (Instagram)/International Space Station Archaeological Project

With this insight, planners of future space habitats will be better equipped to optimize the design of maintenance spaces based on documented behaviors. leading to greater efficiency and possible payload reduction.

Then, there were the nuanced clues to human relations, demonstrating how international cooperation plays out in tight quarters. The presence of something as simple as a packet of Russian-branded dry wipes in the wash case of a German or U.S. astronaut provided hints to cultures of exchange on board – no small matter at a time of increasing global tensions here on Earth.

Not to be overlooked, there was also the baffling mystery of the presence of cake frosting tubes in the galley – surprising, given the lack of a stove or oven on board the spacecraft. It turns out that astronauts Kayla Barron and Thomas Marshburn had made a birthday cake for Russian cosmonaut Pyotr Dubrov, using muffins, honey, and the aforementioned frosting. “This activity,” Walsh noted, “highlights how food preparation is a key vector for reinforcing social relations, even in space.”

Lighthearted as it might seem, the baking experiment is indicative of the resourcefulness of astronauts. Indeed, the continuous occupation of the ISS since November 2000 serves as evidence of the potential for human adaptation to a completely new environment. As Walsh sees it, the ISS is a “micro-society in a mini-world” – the deep study of which will be crucial as interplanetary travel, research and potential settlement plays a greater role in our human story.

ISAAP’s process of systematic documentation and detective work will continue to advance a data-driven understanding of what is required to survive – and thrive – in space.

“As an Ad Astra Fellow, Dr. Walsh is an ideal thought partner for SERC and the USC Department of Astronautical Engineering,” said Barnhart. “Our goal is to expand space stations, long-duration platforms and eventually starships for the human race. This unprecedented research plays a unique role in furthering our shared pursuit, adding that key human element to the discipline of engineering.”

Published on October 16th, 2023

Last updated on October 16th, 2023