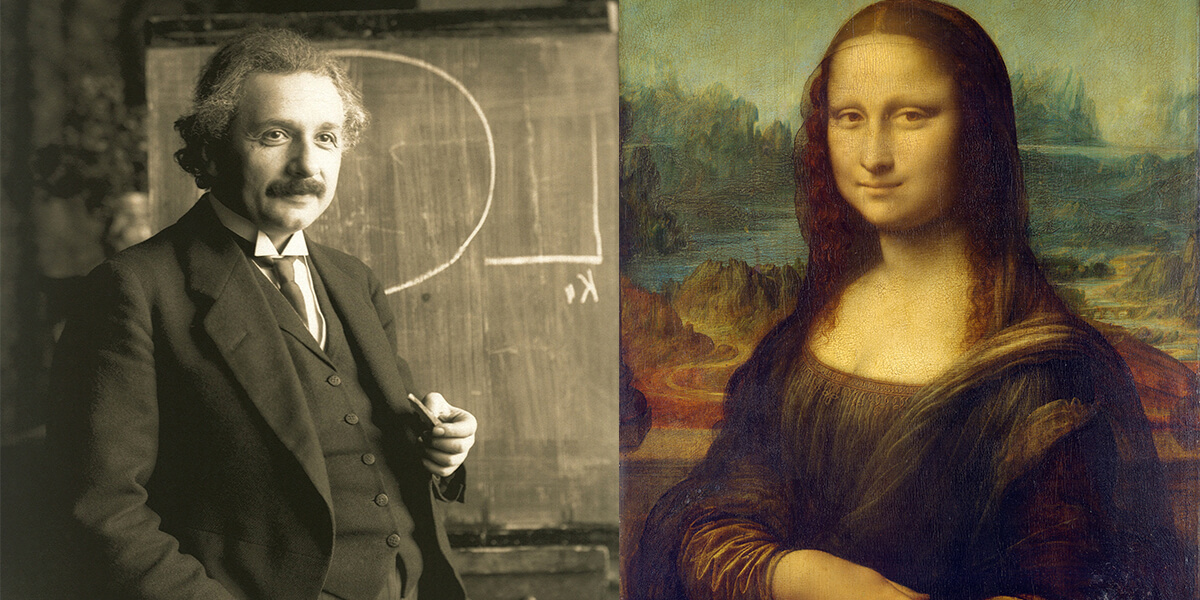

Left: Albert Einstein during a lecture in Vienna (COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

Right: Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci (COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

Left brain vs. right brain. Science versus the arts. What do these have in common? A long history of being seen as opposite ends of the spectrum, like two magnetic poles repelling each other.

But sometimes, when the poles switch and they attract, not repel, a beautiful partnership forms. Take a look at USC Viterbi’s Information Sciences Institute (ISI) and a consortium of 14 art museums across the United States, including the National Portrait Gallery, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Autry Museum of the American West – better known as the American Art Collaborative (AAC).

The institutions are collaborating to implement Linked Open Data in the museums that are AAC members.

So, what is Linked Open Data?

Linked Open Data, often abbreviated as LOD, is about using the World Wide Web to put together data that was previously separated, creating branches upon branches of information that are related to each other. Each new branch can lead to more leaves on the vine and more information to be shared with the world.

ISI Research Director Craig Knoblock, also a USC Viterbi computer science research professor, describes it as “what might be called today as a knowledge graph, that describes the data in a consistent way across the museums and provides connections to other types of resources.”

Prometheus by Paul Manship. The sculpture is displayed the Rockefeller Center in New York. (COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

American Art Collaborative founder, Eleanor Fink, describes it like this:

“Linked Open Data has many benefits. One is that people do not necessarily know where all the works by a particular artist are located,” she said. “They may know for example, that the Smithsonian American Art Museum has works by the American sculptor, Paul Manship Through LOD and the American Art Collaborative, they discover that Colby College Museum of Art, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the National Museum of American Wildlife Art, and Amon Carter Museum of American Art also have works by Manship LOD makes searching for art easier. Fink added “By linking the works, it also brings more visibility to museums, especially those museums that are not located in metropolitan areas.”

“LOD’s value is also about serendipitous discovery of information. By linking archival materials to the works of art (letter, diaries, notebooks), the chance of discovering something new is enhanced.”

How did Linked Open Data bring ISI and AAC together?

It began with a problem and the spirit of inquiry: a common theme in both the fields of engineering and art history.

(COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

For decades, museums have turned to technology to create websites and interactive displays. However, the idea of being able to interconnect the data about the objects in their collections seemed more like a pipedream than reality. Outside the realm of the arts, industry, government, and publishers had learned about and were implementing LOD. In response, ISI had developed some sophisticated tools to convert data to LOD. When Eleanor Fink and Rachel Allen from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, visited ISI and learned about LOD, they realized the pipedream could become a reality. AAC was born. Nevertheless, there were many challenges to face such as the fact that each museum stored the data differently and used local standards for expressing things like dates, dimensions, titles, etc.

That’s one of the issues AAC and ISI attempted to fix.

ISI’s Knoblock said that by “mapping the data to the same terminology or vocabulary, we can know we are talking about the same thing for example, even if the museums used different terms or variations in dates, etc.

But there was one big issue before this could be implemented. Many of the museums didn’t know about Linked Open Data; or if they did, had not implemented yet or did not know how to. Given the nature of Linked Open Data, that’s a problem: if there’s not data to link, the leaves on the vine can wither.

That’s where ISI came in. The organization hosted the discussions with the group of museums that were to form AAC and provided tutorials on what LOD is and how to create it.

Why Linked Open Data?

According to the American Art Collaborative’s website, the reason they chose to use LOD for linked data is because it expands access to cultural history: “deepening research connections for scholars and curators, and by creating public interfaces for students, teachers, and museum visitors.”

Series 1 No. 8 by Georgia O’Keeffe. (COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

In other words, LOD is about connection. It’s about sharing. It’s about bringing people together through a common interest and watching them scurry off to explore all of the ways in which research can grow and develop.

The partnership came with unexpected challenges. “Mapping 14 museums all to the same domain was harder than I expected because we ended up doing it three times,” Knoblock said.

Undergraduate and graduate students took part in the project. The students would each map the data differently, making it difficult to get the standardization required for the project.

Despite this headache and the extra work it entailed, Knoblock found working with the students rewarding.

“It was a really good learning experience, in both terms of the technological pieces and working with students, seeing them learn and mature in the course of the project,” he said.

AAC and ISI have now seen the fruits of their labor.

ISI presented its findings at the International Semantic Web Conference in Vienna last November.

Among the Sierra Nevada, California by Albert Bierstadt (COURTESY/WIKIMEDIA)

With 14 cooperating museums and others interested, it’s only growing, functioning as living proof that when two minds come together, the results can be extraordinary.

“That was the fun part of the project, interacting with people I normally don’t get to interact with,” Knoblock said.

Knoblock said the collaboration has made him wonder how they can they can expand the project to a larger scale.

“Fourteen museums is just a drop in the bucket,” Knoblock said. “What if we wanted to create something that applied to hundreds or even thousands of museums? How would we even do that? I wouldn’t say we have the solution yet, but this generates a lot of interesting ideas.”

Published on April 17th, 2018

Last updated on May 16th, 2024