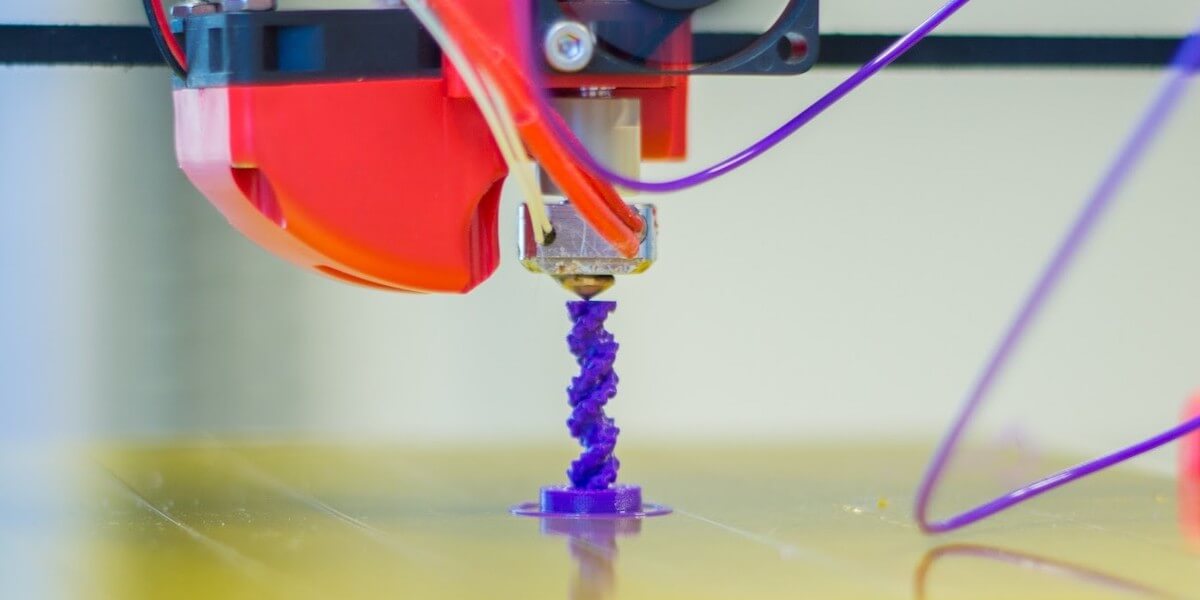

Industrial and Systems Engineering Ph.D. students have developed a system that can detect 3-D printing errors and cancel print jobs before it is too late. Image/Wikimedia Commons

A new system that can detect 3-D printing errors before it’s too late, offering big saving to industry, has been recognized by a leading manufacturing conference.

The work, led by Christopher Henson, with Nathan Decker and Qiang Huang, professor of industrial and systems engineering, chemical engineering and materials science, uses real time modeling to monitor an ongoing 3-D printing build.

The project was recently awarded and honorable mention as part of the North American Manufacturing Research Conference’s student research presentation award.

3-D printing, or additive manufacturing, is growing in popularity as an advanced manufacturing technique, allowing users to directly build customizable objects from computer-generated designs. But 3-D printing also has a high degree of error, causing distortion of printed shapes, resulting in unusable print jobs and excess waste and expense.

Henson and his collaborators use a “digital twin” strategy, creating a digital counterpart of the physical object that can provide an expectation of the behavior of that object in a real life context, in order to detect when a print has failed.

“Our approach captures images of a print as it happening and we are able to simulate what those images should look like based on the 3-D design file the part is printed from,” Henson said.

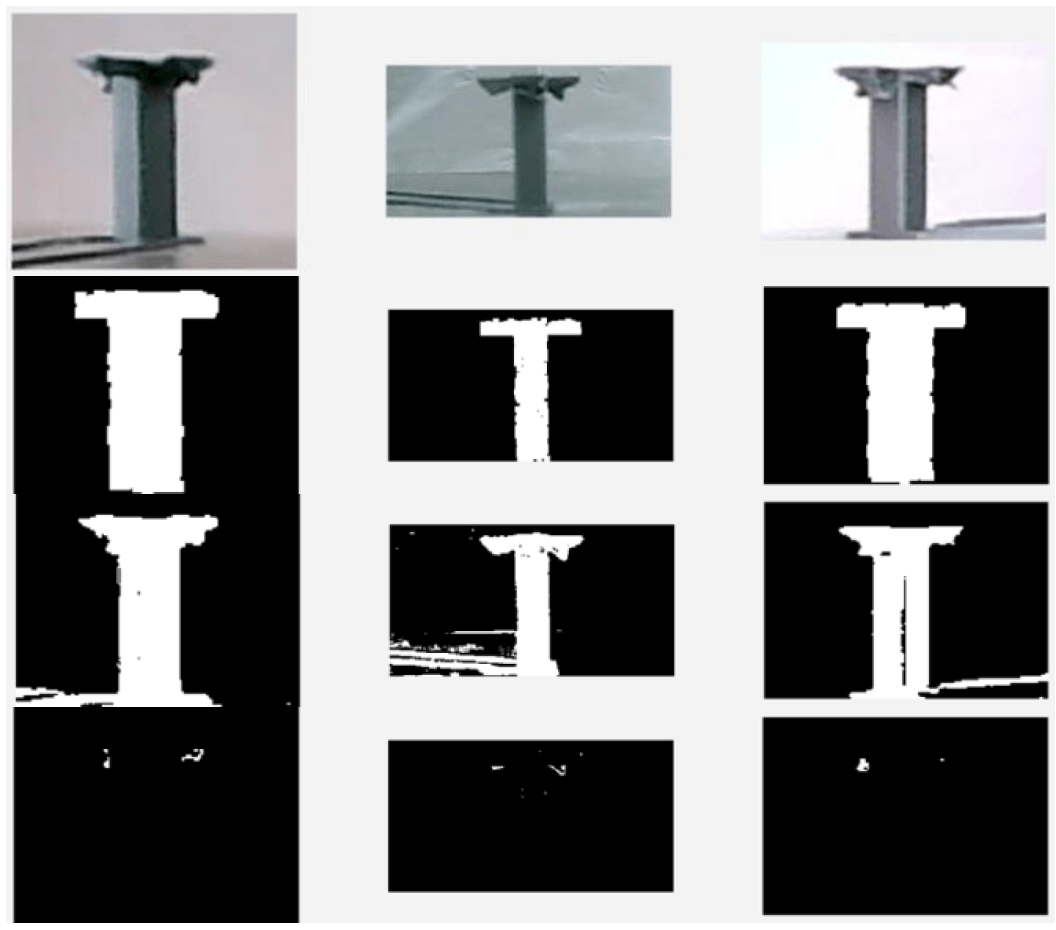

Henson said that by comparing the simulated image with the image the research team captured of the part on the printer, they can determine if there is a major discrepancy that would warrant the cancelation of the print.

A screenshot from the system shows how it can predict where errors will occur in the output of a 3-D print job. Top: A raw captured image from a printer. Top-middle: Simulated image of part. Bottom-middle: Captured image after some processing to identify part and background. Bottom: Comparison showing discrepancies between simulated and captured image. Image/Christopher Henson

“The system we have developed is designed to monitor a print for defects and cancel a print shortly after a major defect has occurred. It has the potential to save manufacturers money by reducing the amount of time and material printers dedicate to manufacturing a failed part,” Henson said.

Henson said that the current industry practice for detecting failure in 3-D printing focuses on the printer by looking for abnormal operation though the characterization of such parameters as acoustic emissions or the temperature of the extruder—the printer part responsible for drawing in, melting and pushing out the filament.

“Our approach focuses on the part being printed rather than the machine,” Henson said. “This means our strategy is capable of detecting deformation both when the printer is operating nominally and when it is not. Our approach is also capable of accounting for a non-stationary print volume which is a marked advantage considering a minority of machines have a stationary print volume.”

Henson and Decker are also working with Huang on a new software platform to improve 3-D printing accuracy by 50% or more.

Published on June 29th, 2021

Last updated on June 29th, 2021